Underthinking Racism

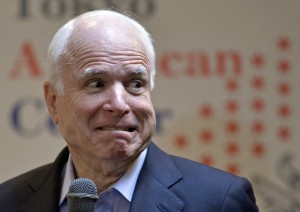

In 2000, while speaking of his time in a Vietnamese POW camp, John McCain said “I hate the gooks. I will hate them as long as I live.”

During the last few months, and especially Black History Month, I have spent a lot of time reading responses to and ideas about ways of responding to spoken/written instances of racism. The thing that consistently jumps out is that intelligent people were often cowed by people who were louder, angrier, and more willing to deflect scrutiny rather than examine their deeply problematic sentiments. Responding to racial microaggressions is also problematic for people who object to racism because they are accused of being “too sensitive,” “nitpicky,” “always wanting to argue about everything.” The objections are washed away by lazy sidestepping. So what is the strategy for debating with people who intimidate and take away our rhetorical ground? Start from a different, unexpected place: absolute directness.

This isn’t about discussing nuances of intersections of identity, because those discussions are had by participants who are willing to respect one another’s ideas even if they don’t agree. It is precisely this respect that is missing in everyday confrontations with racism. There’s a feeling of impotence that goes with knowing all of the reasons someone is wrong but then being shut down because the offending party counters with their own indictment. You are accused of looking for trouble and overreacting, a bit of misdirection away from the original offense. When having a critical discussion with someone you know respects you and your ideas, you usually shelve simple phrasing and aggressive language. But when you are confronted by someone who starts an interaction by disrespecting you, it is disadvantageous (emotionally and for the sake of your argument) to put those rhetorical tools aside.

In 2010, Jake Knotts, a state senator in South Carolina, collectively referred to President Obama and Governor of South Carolina Nikki Hayley as “ragheads.”

I think it’s especially important for intellectuals, because we train ourselves about all of the ways we need to respects other people’s voices and then we are blindsided when we are assailed for requesting something so basically decent and polite as not using racial slurs (for example). As cultural critics and social justice advocates, not responding to instances of everyday racism does not and will not feel acceptable. What follows are instructions and preparation for the ugliness of the nature of these sorts of conversations. It’s not about dehumanizing the person you find yourself confronted by, but empowering yourself to be direct, honest, and angry when it is called for. It’s about preserving your sanity and getting ready to do whatever you can to change some minds.

1. Be prepared for personal disrespect

Many people have been acculturated to perceive any questioning or push back as an attack. They can react aggressively, verbally or physically. This is a way of trying to intimidate you into withdrawing your opinions. It happens particularly often with racism because racists usually understand that accusations of racism are akin to character assassination. They’re not wrong in that respect– it should be considered a shocking breach in a person’s moral character– but they believe they are being unfairly persecuted to be named as such. Unless you feel your safety is being threatened, see this intimidation tactic for what it is: a person resorting to threats because they grasp the logical inadequacy of their position.

Larry Taylor, a Texas State Senator, complained to a colleague in a public hearing “Don’t nitpick. Don’t try to Jew them down.”

2. Be prepared for deflection

You will be accused of intolerance. You will in all earnestness be told that being intolerant of racism is as bad as racism. You will be told that you are the one who is “making it about race.” People guilty of racism will not take responsibility for their racism when confronted with evidence of it. They employ deflective responses about the sensitivity of the person offended. They believe that saying someone is “overly sensitive” is a legitimate response to objections. These all amount to the same thing: Racists want speech free of consequences. People who commit racism complain about under the phrase “political correctness,” but most people call it “politeness” or “ordinary decency.”

3. Be prepared for honestly repugnant ideas

In some ways this is the hardest, even though it seems like the most obvious. It is difficult to process exactly how terrible a person’s ideas about race can be. There are two things that can happen in every interaction, and it’s important to be ready for both. The first is that you stay and engage the person who has said or done something racist. If that is your choice, remember that sometimes you just cannot change someone else’s opinion; it’s not your fault if you can’t get through to someone. If you know the person you’re engaging with, especially if you know them well, this can be hard to accept. The second option is to leave. No matter how strong an advocate you are, you are never required to put your emotional health at risk, and sometimes that means walking away. It’s okay and necessary to pay attention to how each situation affects you.

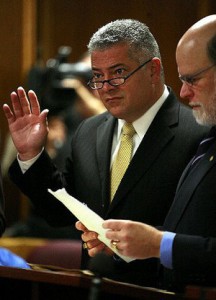

Ralph Arza, a state representative in Florida, called a state superintendent a “negro mierda” (“black piece of shit”) in 2006.

4. Know the most common arguments and be ready to answer them concisely.

Think about it like triage treatment of racism.. If it were in a surgical suite (e.g. cultural studies conference) you would be able to give their arguments complicated answers and engage in conversations that took decades of training. But if you’re in the E.R., confronted with a gaping wound, you have limited time and resources to devote to the problem.. There are situations in which you cannot draw on your vast aquifers of knowledge, and it’s important to consider beforehand what you will do when confronted with unexpected racism.

This is especially true because racists seem to think that if someone cannot immediately give them an explanation for why their behavior is racist, then they have won– the absence of a straightforward answer feels like triumph for them. That is an awful feeling.

5. Be prepared to take it personally, which is incidentally what you will be told not to do.

You will be told not to get upset when someone confronts you with their wildly upsetting behavior. But, more than anything, this essay is here to tell you to be angry, assertive, impassioned, and upset. Getting angry is not a failure, in part because civility and good manners are tools for quieting dissent, and there is nothing civil about racism. If the situation calls for it, yell at them and do not let anyone make you feel bad for doing so. Curse. Racists will blame you for being offended by their bigotry, so you have to remember and articulate that their vile, repugnant ideas are the things that should be apologized for. Establish yourself as the kind of person who will not put up with bigotry. Set an example for other people. Fight racism everywhere you see it. Someone more vulnerable than you probably wishes they could.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.