Shriek When the Pain Hits: Form, Feeling, and Violence in the Inflammatory Essays

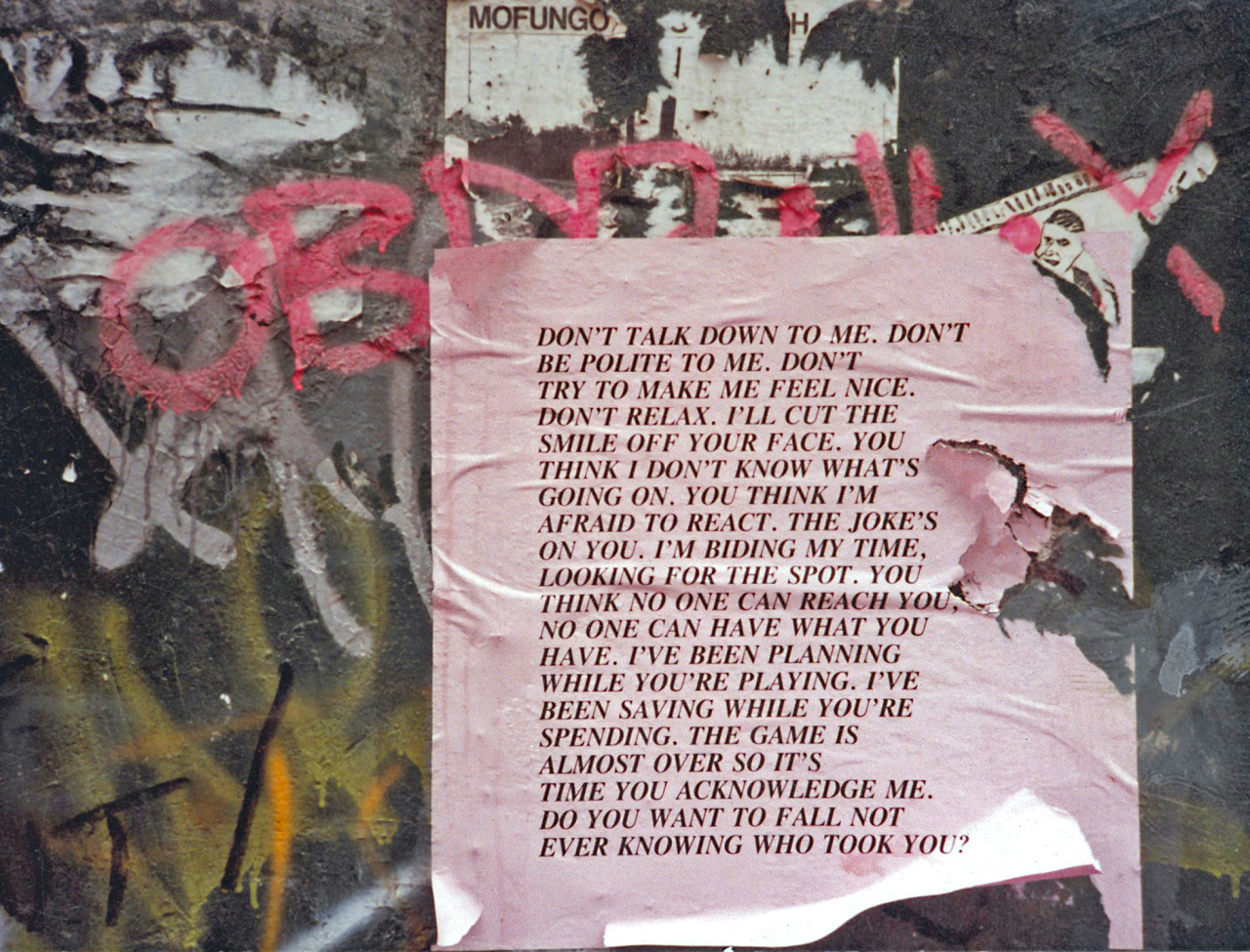

Between 1978 and 1982, the artist Jenny Holzer created a series of 24 printed manifestos and posted them on buildings in New York City. These Inflammatory Essays, now typically encountered in art galleries, raise key questions about the visual nature of words and the narrative aspects of images. By projecting language into the landscapes of the city and the gallery, Holzer disrupts not only the everyday life of passers-by, but also the disciplinary boundaries that separate art, literature, and popular culture. Moreover, Holzer’s invocation of shocking violence becomes a particularly visceral meeting point of the literary and the visual. By defamiliarizing the street and the gallery space through violent language, the Essays trouble the boundaries between text and audience. They also emphasize a set of phenomena embedded in visual and literary culture in which language and image are mutually constituting, the one shaping the affordances and affective power of the other.

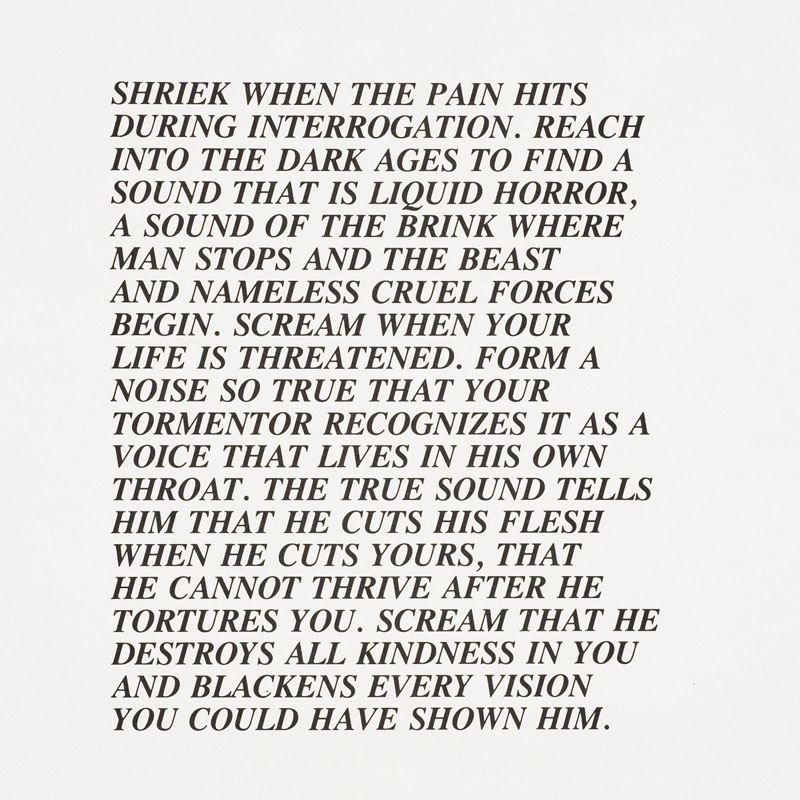

The Essays take inspiration from 20th century revolutionary figures ranging from Emma Goldman to Adolf Hitler. Each manifesto is composed of 100 words, arranged in twenty lines of roughly five words each, and printed in all-caps, italicized Times Roman Bold font. In the gallery space, the Essays are often repeated and will cover an entire gallery wall with 17×17 inch pieces of brightly-colored paper. In later years, Holzer began to present excerpts of the essays in her signature LED light displays. Although quite different, both formats make repetition a defining characteristic of the Essays, pointing out the ways in which the context of the Essays remakes their form, and their form modulates audience response.

Literary scholar Caroline Levine’s recent work on the affordances of form is instructive for thinking about how the Inflammatory Essays use language and image to provoke strong feelings. Levine borrows the term affordances from the design world to “describe the potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs.”[1] Just as the affordances of a fork are different from those of a knife—both can stab, but only one can slice—so are the affordances of an isolated Essay different than those of a large-scale installation of the complete Essay series. Likewise, the form in which Holzer portrays acts of violence—succinct, sometimes circumspect language, printed in a block of text on colored paper—does a different kind of work than a photograph, film, novel, or painting can. On the one hand, by presenting violence through language, with a minimalist aesthetic, Holzer modulates the shocking jolt that an image might deliver more forcefully. On the other hand, she manipulates the affordances of language to direct the threat of violence more directly toward the viewer, using a linguistic form that seems less direct than the visual to build a sense of threat and encourage audiences to picture acts of violence in their minds.

Image via Pinterest

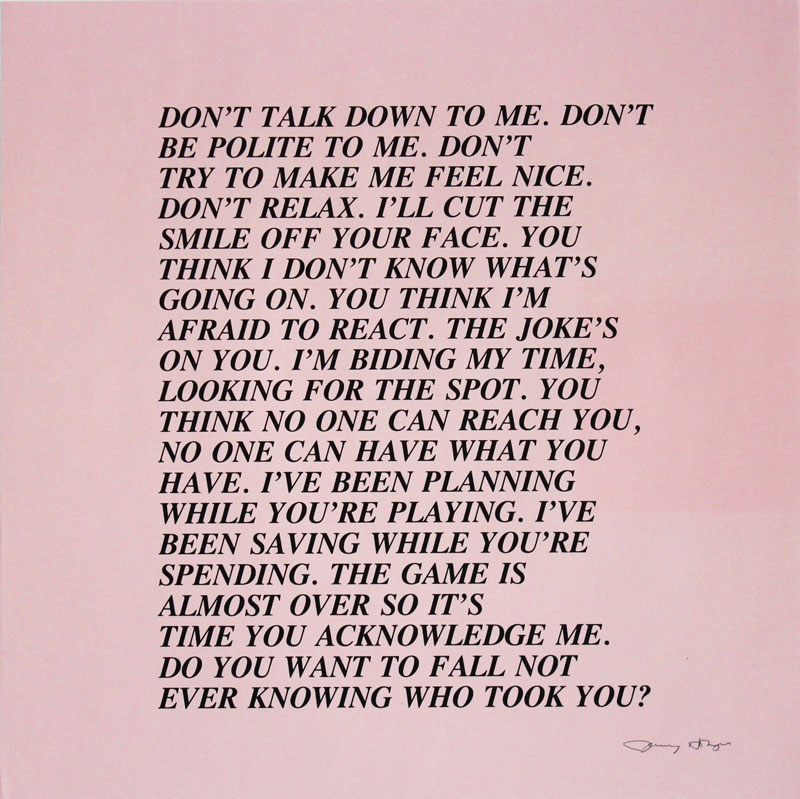

In “DON’T TALK DOWN TO ME,” Holzer modulates feelings of threat, anger, and revulsion through linguistic and visual aesthetic choices. This essay, which as far as I can tell is always printed on pink paper, features a speaker that moves quickly from self-possession and assertiveness to disturbing threat. As I read the first lines of the essay—“DON’T TALK DOWN TO ME. DON’T BE POLITE TO ME. DON’T TRY TO MAKE ME FEEL NICE”—I can picture myself saying them to the men who explain things to me. I am annoyed, and right, and reasonable. Yet the essay moves into a different realm in the fourth and fifth line, when the speaker threatens the viewer with physical violence: “I’LL CUT THE SMILE OFF YOUR FACE.” Suddenly, I’m no longer aligned with the speaker; I’m the problem. The essay threatens violence at readers’ faces, eliciting a visceral sense of shock. When looking at the piece, it’s difficult not to reach a hand up to your own smile to remind yourself that it’s still there.

The emotional power of the Essays emerges from the juxtaposition of violent language and minimalist aesthetics. Viewers’ affective responses are also manipulated through the different ways they encounter the essays. A large wall of colored squares of paper affords audiences the opportunity to experience Holzer’s work as both a large-scale conceptual installation and a close-up reading experience. In the span of time it takes to read each essay for the first time, a viewer might succumb to the stupefying effects of what Sianne Ngai calls stuplimity—a combination of shock and boredom.[2] Agglutinated violence at this moment has the effect of overwhelming just enough to produce fear, dread, discomfort, or shock. Reading the individual essays is quite a different experience from stepping back and taking in the installation as a whole, and this scalar shift effects an aesthetic one, as well. In close proximity, the Essays work primarily as language, but from a few feet away, the words fade from view.

The earliest audiences for the Essays saw them on the sides of buildings in Lower Manhattan; later audiences encountered them in art galleries. I’ve encountered the essays online. Never having seen them in an art museum, I am like the many people who experience the Inflammatory Essays as Pins to scroll through, or as part of well-curated Tumblrs. Holzer has reprinted lines from the Essays and her Truisms series on benches, t-shirts, bumper stickers, movie theater marquees, the sides of buildings, and Twitter. Each of these forms reshapes the work done by her words. As the Essays have been incorporated into the digital world, they’ve taken on, I would argue, a feminine connotation as part of the Internet of Aesthetic Pleasure. They’re all over Pinterest because they’re beautiful. They belong beside those Céline ads featuring Joan Didion.

Screenshot by Author via Pinterest

This is not to suggest that the newer, digital form of the Inflammatory Essays erases their subversive power by coding them as feminine and chic. As Levine argues, the gender binary is itself a form that organizes the sociopolitical world.[3] In a work of literature or art, she contends, multiple forms—aesthetic and social—collide with one another to create new kinds of meaning.[4] When the Inflammatory Essays are re-formed as Pins, we should not presume that the girly consumerism typically associated with Pinterest trumps the other formal features at play in the Essays. Rather, new affordances emerge in this conjunction, which can lead to new aesthetic and affective encounters with the violence presented in the Essays.

Indeed, the Internet may be the place where the Essays are their most violent—or, put another way, where viewers are most absorbed in the violence they describe. Although in this context, the Essays resemble the #inspirational messages that proliferate across Pinterest and Instagram, they are also reframed as primarily visual. One of the affordances of Pinterest lies in the way it encourages both scrolling through many images and lingering on one image. Scrolling emphasizes the vibrant minimalism of the square pages and evokes artists like Josef Albers and Piet Mondrian. By contrast, clicking on an Essay makes viewers susceptible to the unsettling feeling of being commanded to “SHRIEK WHEN THE PAIN HITS DURING INTERROGATION. REACH INTO THE DARK AGES TO FIND A SOUND THAT IS LIQUID HORROR, A SOUND OF THE BRINK WHERE MAN STOPS AND THE BEAST AND NAMELESS CRUEL FORCES BEGIN.” Rather than domesticating the Essays, digital platforms can enable feelings of shock, which “[smash] into the psyche like a blunt instrument.”[5]

Art, according to cultural theorist Renee Hoogland, is experienced as an event—it doesn’t so much use a system of signs to make meaning as force the viewer into a field of experience, a stew of embodied sensation, cultural associations, and emotion. As she puts it, “We see images rather than read them. Aesthesis, in the original sense of feeling, sensation, or perception, therefore marks an affective experience.”[6] The Inflammatory Essays bridge a divide between the workings of language and the workings of image, and thus demonstrate what’s missing in both our understanding of language as an endless chain of signifiers and in Hoogland’s attempt to correct it. Hoogland contends that art is about affect—the encounter you have with an artwork is one of sensation and feeling, rather than linguistic interpretation or decoding.[7] Joining a chorus of scholars who are part of the recent “affective turn” in cultural criticism, Hoogland defines affect as “the experience of embodied intensity that cannot be fully captured in language, nor fully determined by form nor by the chains of signification.”[8] As I’ve argued, the Inflammatory Essays provoke such an “experience of embodied intensity,” but they do so as images composed of language.

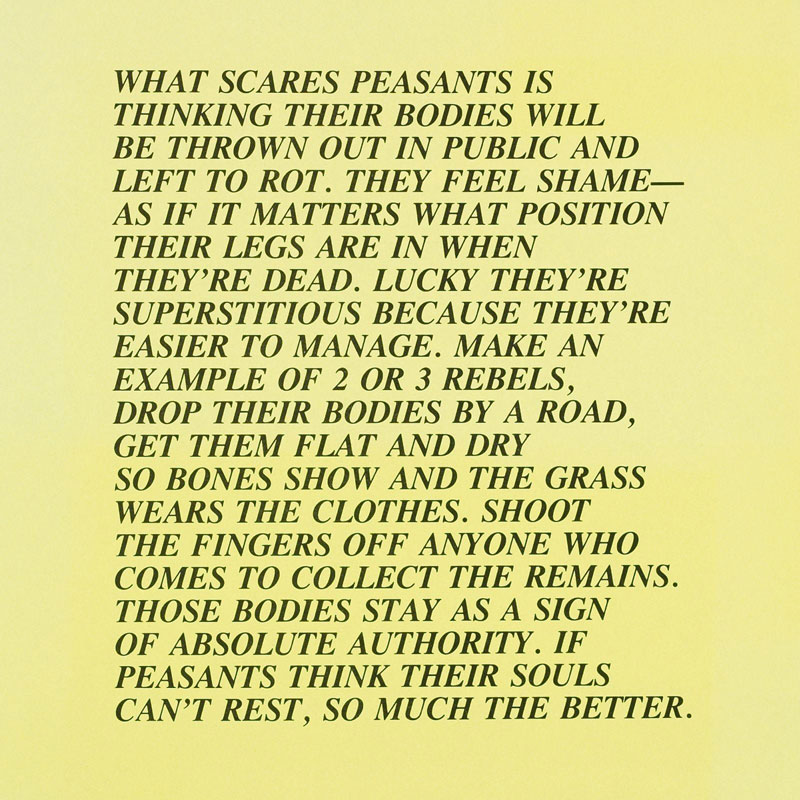

Image via Pinterest

The Essays are inseparably linguistic and visual. This formal hybridity also triggers an exchange between form and feeling, doing the work of moving viewers by articulating and withholding images of violence. When I read a line like “MAKE AN EXAMPLE OF 2 OR 3 REBELS, DROP THEIR BODIES BY A ROAD, GET THEM FLAT AND DRY SO BONES SHOW AND GRASS WEARS THE CLOTHES,” I feel a kind of shock, a shiver of vulnerability and repulsion. Where does it come from? Not from seeing a body broken or suffering, or even from being inundated with details of torture. In contrast to an image of a suffering body, a linguistic representation of violence would seem to soften the feelings of shock, fear, or disgust audiences might feel. Yet images also fix the visual representation, drawing a kind of boundary around the horror that language withholds. Holzer’s visual form further emphasizes the linguistic withholding that allows viewers to picture the gruesome acts described. The colored paper and squares of text soften the affective jolt of the violence described, but this softening also returns viewers to their own vulnerable bodies.

In the Inflammatory Essays, Holzer makes aesthetic choices that remove many of the threads that connect what’s described on the page to what might be experienced in the world. In particular, she removes images of the violated body and a coherent speaker who is motivated to violence by a consistent set of beliefs. The Inflammatory Essays are characterized by a refusal to paint a full picture of the violence they invoke. Their form erases many of the visceral or narrative threads that tie the words in the Essays to the acts of real-world violation that I might picture when I read them. Yet the Essays are still capable of shocking or repelling audiences, and these affective responses are tied to the body. A strong affect is felt in the body—the jolt of shock, disgust, terror, even laughter overtakes the body violently. And a phrase like “I’LL CUT THE SMILE OFF YOUR FACE” can provoke such an affective jolt. It’s not just that words play off each other in a system of differences to make meaning; they call forth the body through their chain of associations, and remind us of our vulnerability to pain.

[1] Levine, Caroline. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2015. 6.

[2] Ngai, Sianne. Ugly Feelings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2006.

[3] Levine, 14

[4] ibid. 16-18.

[5] Felski, Rita. Uses of Literature. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 113.

[6] Hoogland, Renee C. A Violent Embrace: Art and Aesthetics After Representation. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2014. 2.

[7] ibid. 15

[8] ibid. 14. For Silvan Tomkins, widely considered the originator of affect theory, affects are precognitive and universal, although they are profoundly mediated by culture. Tomkins defines nine affects: Joy, Interest, Surprise, Anger, Disgust, Dissmell, Distress, Fear, and Shame. For an overview of Tomkins’s work, see Eve Sedgwick and Adam Frank, Shame and Its Sisters: A Silvan Tomkins Reader. Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 1995.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.