Rethinking the Creative Class: Toward Creative Resistance

It’s no underestimation to say that creativity as an industry has transformed our economies and society in the West, particularly the cities. In the UK yearly revenue stands at about $11.64 billion a year, while in the States and Europe as a whole those figures are $620 billion and $710 billion.

And if more corporate industries like TV, advertising, marketing, digital and artificial intelligence are lumped together with the creative arts, with the former being the high earner and the latter its impoverished cousin, the social shift is still significant. Making money out of the post-industrial landscape and inner city decline is something of an achievement.

Yet in the era of Brexit and Trump, the one-sided celebration of the creative economy has come under fire. Even its main proponent, Richard Florida, has recently argued that the cultural industries may be responsible for, or at least intersect with, a new class divide within cities. The jubilant celebration of our urban creative centers has turned to soul searching and self-blame.

But is the creative class really at the core of the massive inequalities in our society? And how should socially conscious artists and creatives position themselves in the midst of these rifts? In short, how do we get the cultural advancement that creatives deliver and resist the exclusionary processes of gentrification?

Florida’s thesis – the new urban crisis

The shape of Florida’s new book, The New Urban Crisis, was finalized in the wake of Trump ascendency to the presidential throne. And although Trump did not win on numbers alone, the Electoral College, which plays on the new spatial divide between urban and rural, worked to his benefit. A similar process was at play in the UK, with both Brexit and the 2017 election showing a marked voting preference disparity between the cities and those outside.

Pundits have claimed that rural and small town environments are the new “left behinds” and that self-serving metropolitan elites of, in the main, London/New York, are to blame.

How did this happen? Well, according to Florida, in the knowledge and cultural economy, people and talent matter. He refers to the concept of “clustering” to describe how wealth is generated by concentrations of skilled people living and working densely in a small place. In the country, skills are fewer, and people are dispersed. Its luxury of space, slower pace of life, and social isolation condemn the rural to economic decline. Those with aspirations race to the clusters of wealth and talent—and they leave the rural behind and transform cities into playgrounds for the wealthy.

The problem of governance

This new spatial divide creates a problem of governance. When cities have very different needs from towns and rural areas, and where even within cities localities have very different dynamics, national policy doesn’t really cut it. This problem is particularly apparent when the government, of whatever hue, doesn’t represent the people as a whole, only its political constituent. Florida advocates a new form of decentralization, where place is imagined by the people who live in it, and rather than live as a unified nation, we “agree to disagree.”

We may want to comment ironically, in passing, that when the boot was on the other foot, the decline of the inner cities around the 1970s wasn’t a cause of anxiety or action for the governing class. I’d argue that the revival of the cities into the economic powerhouses they are today was down to a lot of hard work by Bohemian rebels, who used the empty spaces left by industrial decline to do cultural experimentation, as Sharon Zukin notes in her thrilling book Loft Living (1989).

And as such, we may also question why rural areas and small towns can’t put a similar energy into reviving their areas, instead of turning to right-wing populism that sometimes sounds uncannily like collective whining.

Let’s look at the issue from another angle – the problem of gentrification.

Gentrification is not all bad

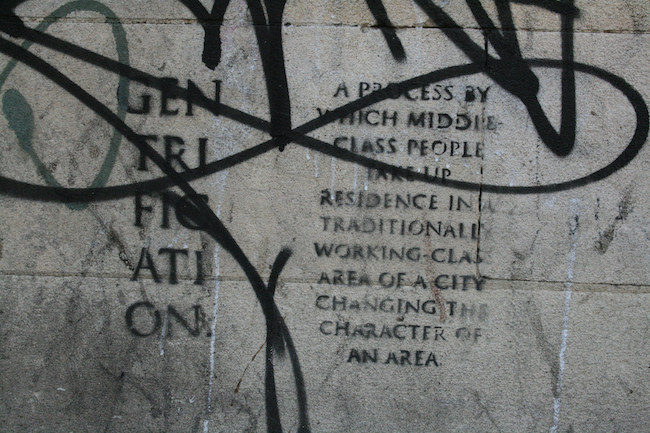

Gentrification has become the concept to describe everything that is wrong about cities from the standpoint of its inhabitants. The term was first used by Ruth Glass in 1964 in a collection of essays called London: Aspects of Change. She argued gentrification was a process, observable in the 1960s, where the middle classes invaded a working-class area, turning modest working-class housing into upmarket residences.

Doris Lessing, in her writings on London (The Four-Gated City or The Golden Notebook) also referred to a middle-class hippie or bohemian urban style of sanded floors and white walls. It was symbolic of a rejection of the suffocating style of wallpaper, carpets and home, family and work culture of the working class and lower middle class.

And it was not just the middle classes; rather, as subcultural theorists always observed, change was enacted by an energetic combination of the intelligentsia and upstart working-class youth who wanted to live differently, whether as creatives or revolutionaries. It was a cultural transformation that would take us through to the early 1990s.

But the places Lessing describes had already been abandoned in the destruction of the war; the movement of the radically motivated middle classes into the cities saved its housing stock. Indeed, in the UK at least, their activism prevented local councils from destroying all the Victorian and Edwardian housing in favor of tower blocks and council estates.

Sharon Zukin also observed a similar process in New York. Industrial spaces that had been left to rot in the collapse of heavy industry and inner-city trade were taken over and revived by artists. Then, of course, they were bought by the wealthy who viewed culture as something to purchase rather than earn. House prices escalated; artists were forced out. Like Jane Jacobs, who describes a parallel situation in the high street, Zukin depicts a short period of struggle for change and innovation followed by cultural sanitization.

But the problem is less culture and more economy. The remaking of cities coincided with a revival of right-wing libertarianism, which celebrated the free markets and the diminishment of the role of the state. All public goods, from culture to housing, became gradually converted into commodities. In this context, art becomes a bourgeois amenity and a tool of urban boosterism used to prime areas for development and the expansion of the playgrounds of finance capital (for example, Spitalfields and Bethnal Green in London).

But more recently (in the UK at least), as the wealthy run out of centrally located, convenient, and creatively inhabited spaces to cannibalize, “gentrification” takes a different pace. The arts and creativity become a way of tackling urban and small town neglect. Areas that effectively warehoused the working and jobless poor, with few amenities, are being reimagined by placemakers and creatives and, I’d argue, potentially in a more inclusive way.

Is that so bad? It depends very much on intent and how far activists and government support the benefits of community co-creation. But it is a long way from the vision of exclusive urban clusters described by Florida.

So what can creatives do to prevent the turnover of places to wealthy playgrounds and promote a more inclusive society?

Creative resistance

Creative workers need to resist. And resist not just against the process of cannibalization, but also against the renewed trend in politics to reclaim or restore the primacy of the “rural sensibility” against metropolitan culture, and in doing so destroy what has been built.

We surely need to feel no guilt about the successes of urban renewal, particularly given that all creatives, except the most capitalized businesses, are themselves impacted negatively by increased land values and development (where is all the studio space going?). Art is a tool, not an instigator, of gentrification. For example, one commentator examined the very different role the arts were playing in Detroit, a place in which capital is (currently) not interested.

And artists and creatives are mounting their own critical response, somewhat selflessly (because as a freelance writer I can confirm that political resistance narrows your pool of potential clients), reshaping political language through the lens of the visual, poetic language, fiction, and digital engagement.

Hands off Our Revolution is an artistic and political response to the new politics. The Boyle Heights Alliance in Los Angeles directly tackles the role of imposed art and the marketing of cultural identity for urban boosterism. London-based Southwark Notes is also leading the way in questioning the role the arts play in urban boosterism and calls on artists to take a critical stance. I could list hundreds of projects rethinking creativity, place, and community in the UK and globally.

But how do creatives shape space, as our hypercapitalism continues to swallow it up (literally, in the case of the Grenfell Tower fire in London’s Kensington)?

I’d argue that the creative sector needs to rethink its practices in favor of greater social inclusion and fair pay for a fair trade. Creativity can’t be claimed and protected as a middle-class or elite profession. And rather than carving out spaces for cultural exclusivity, as has been the practice of the past, creative people need to reach out and engage with communities (not for the purpose of ironic depiction but education and advancement on both sides of the divide).

The practice of collaboration, creating a stronger sense of common purpose as well as individually driven creativity, also would be a positive move. People could work together on co-created community projects and information sharing.

The creative sector may have a critical role to play in the core source of urban inequality—housing—whether it’s by having a compelling voice arguing for justice, challenging planning and development decisions, or visualizing and designing a different way of living.

There is a role for local government here too because undercapitalized creatives (in other words, most of us) don’t have the resources to acquire land or the capacity to reach out. Making land available for use at low or no rent, as studios and training facilities, and offering small grants for specific projects, allows creatives to use their time for community activity. Local government could also sponsor arts training for low-income people, given that successive right-wing governments are squeezing creativity out of public schooling.

None of this involves a loss of the particularity of creative purpose. It means having a greater social vision too. The mechanics of what we call gentrification don’t benefit most creative workers either; it just creates a new creative division of the haves and have-nots. So let’s use our voice to change it.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.