The Visual World of Girls

When Girls first premiered on HBO in 2012, the reviews were mixed. While Emily Nussbaum, writing for New York Magazine, confirmed the show was an important televisual text of the 21st century, Gawker’s John Cook dismissed the show for being “a television program about the children of wealthy famous people and shitty music and Facebook and how hard it is to know who you are and Thought Catalog and sexually transmitted diseases and the exhaustion of ceaselessly dramatizing your own life while posing as someone who understands the fundamental emptiness and narcissism of that very self-dramatization.” The New Republic’s David Thomson was less dismissive but suggested show creator and writer Lena Dunham’s worldview was too limited and should expand to Orson Wellesian stories of “the failure of American wealth and power.”

Dunham took on this type of criticism head first in a storyline in the first season. In it, her cynical friend Ray (Alex Karpovsky) supplies Hannah (Dunham) with a list of “real things” the budding author should write about:

“Cultural criticism. How about years of neglect and abuse? How about acid rain? How about the plight of the giant panda bear? How about racial profiling? How about urban sprawl? How about divorce? How about death? How about death? Death is the most fucking real issue. You should write about death. That’s what you should write about. Explore that. Death.”

That advice turns out to be sorely misguided for Hannah—and it also doesn’t do justice to Dunham’s skills as a storyteller. The critics above, along with this brief example from the show, highlight how often (though not always) critiques of the show fell along gender lines, with female critics validating the show’s importance and male critics failing to see the merit of a show centered on the intricacies of relationships.

However, more recently the show has garnered artistic credibility, particularly because of its trademark “bottle” episodes—episodes with a limited cast, set in a highly specific location. Throughout its five seasons, Girls has been at its best when show creator and writer Lena Dunham is able to tell contained stories that stand alone from the series arc. Though these stories lack the sweeping historical gestures of Citizen Kane, they are equally as powerful.

In the episodes “One Man’s Trash,” “Beach House” and “A Panic in Central Park” Girls goes beyond its usual cinematographic style to craft images that evoke contemplation and create a sense of intimacy. The opening sequences of the latter two episodes set the stage for the entire episode tonally and they introduce the visual metaphors that will bend and reshape as the story develops. In “One Man’s Trash,” Hannah enters a world momentarily, escaping the drudgery of her millennial romantic and work life.

In these three episodes, Dunham’s sophisticated storytelling is accompanied by a visual sensibility that enhances the world the characters inhabit.

One Man’s Trash (Season 2, episode 5)

In “One Man’s Trash,” Hannah (Dunham) gets to live out a movie—like romantic fantasy. She meets Joshua (Patrick Wilson), a handsome doctor whom Hannah has been inadvertently frustrating by filling his trash cans with trash from her job. When she goes to apologize to him, he invites her into his house.

As Hannah accepts the invitation to enter the house, subtle otherworldly music begins to play. Is he dangerous? Is she walking into a bad situation? This brief but crucial musical cue (which returns only during a tense moment before they kiss) sets the tone for a fantasy—filled day where Hannah gets a taste of what it’s like to “be an adult.”

“Ok, this place is unbelievable […] Like, I didn’t even know a house like this even existed in my neighborhood. […] I feel like I’m in a Nancy Meyers movie.” Though Girls is often charged with its narrow world depicting unlikeable white, privileged women, this episode also demonstrates Dunham’s understanding of the strata existing within the privileged class. As much as the young women of Girls have financially secure to well-off parents, they do not inhabit the spaces of Nancy Meyers’ characters. That world excludes even Hannah.

Thus Hannah moves through the space with curiosity and care. She cradles a glass of lemonade. She slowly runs her hand along his meticulous hanging dress shirts. She sits at a table with quiet composure.

They lounge. They have sex. They play games and read books. Their leisure time is domestic and timeless. Their time together is idyllic and carefully composed. The blissful setting is almost too much to bear. At one point, Hannah passes out in the shower, utterly soothed and dreamy.

This moment is reminiscent of a scene in Sex and the City when Carrie (Sarah Jessica Parker), overwhelmed by the romantic declarations of suave Russian artist Aleksandr Petrovsky (Mikhail Baryshnikov), literally swoons, falling into his arms.

A photograph of a woman hovers over them, both a specter of Joshua’s ex-wife and an image that reminds the viewer of the Hollywood blonde bombshell type for whom romantic stories like these are written. While Hannah is curled in an anguish-ridden ball, the women in the photograph lays on her back, serene–perfect as a picture. [Hannah in Bed.jpg]

Beach House (season 3, episode 7)

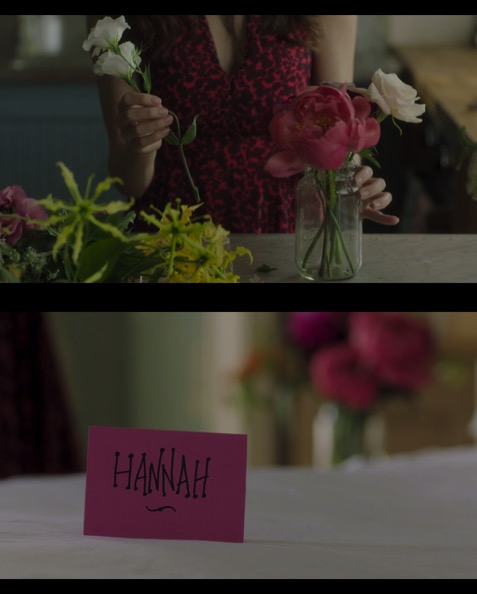

The episode “Beach House” begins unusually. Cheerful violins play as we see a closeup of Marnie (Allison Williams) preparing fresh flowers. She makes her flower arrangement and proceeds through a white, bright house. She places name cards gently on the mattresses, she adds flowers to the rooms. The spicatto strings function the way the Downton Abbey theme music does: they recall an earlier time and give a sense of movement and purpose to the scene. The use of 18th century style music for this scene is also a jab at Marnie’s overly formal reception of Hannah, Shoshanna (Zosia Mamet), and Jessa (Jemima Kirke). Where Marnie think she is merely being a dutiful host and caretaker, the audience sees this scene with humor—seeing that she has here, like in the rest of the season, held expectations that are almost ridiculously too high.

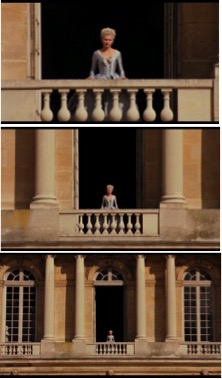

Marnie opens a pair of balcony doors, and the camera soars around to a front view of the titular beach house. The sight is impressive, and the camera pulls back to reveal the magnificence of the place, with Marnie at the helm, taking in the view. This lofty camerawork signals the historical weight of the episode. A similar shot occurs in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette.

Though in Girls, the shot also plays with irony, the episode is a turning point in their relationship that sets the tone for the way their bonds dissolve in the next couple of seasons.

The beginning of this episode runs counter to the shenanigans while they are at the beach house. Marnie carefully, and neurotically, put together a bonding syllabus for the girls, but her plans are derailed. By showing us Marnie’s efforts at the top of the episode, the end point becomes more disheartening. What began as a trip full of possibility ends with the women yelling at each other and telling each other their worst judgments. The next day, as they wait to leave the beach, they dance in unison, recalling the brief moments of fun they had but also holding on too dearly to relationships they know are not fulfilling.

The Panic in Central Park (Season 5, episode 6)

This episode was inspired by the 1971 film The Panic in Needle Park, a grim film about two drug addicts in love who spend the day together in New York. In the episode, Marnie is intoxicated with the idea of getting back together with her ex-boyfriend, even if that is not the healthiest decision.

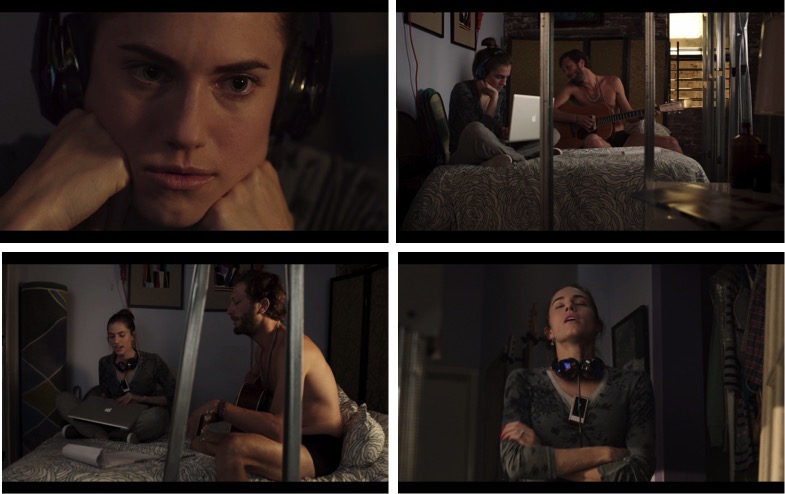

The episode begins with a tight close-up of Marnie’s face. The camera pulls back to reveal her in a corner hovering over her laptop as her new husband, Desi (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), plays his guitar. The tight space of their apartment appears even more constraining as the shot captures row after row of vertical lines that, instead of extending the frame, act as prison bars, trapping Marnie in a loveless marriage. The lines also neatly divide the feuding couple, solidifying their divide through cinematography. Even when Marnie leaps out of the bed to yell at Desi, vertical lines behind her close her in. The walls, the row of shirts, the guitars behind her, visually clutter the space and make it not a cozy but emotionally chaotic space. The closed frame tells us everything we need to know; the shot is set up so that off-screen space almost doesn’t exist.

When Marnie leaves the apartment she is followed by vertical lines and frenzied shapes in the subway and on the streets.

Finally, as she passes by a group of men, the frenzy starts to give way. Her ex-boyfriend, Charlie (Christopher Abbott) sits among them as they catcall her. He notices her. He says hi, and Marnie is astounded at Charlie’s voice. The reverse shot of the exchange is a closeup of Marnie.

The background is out of focus but suggests an expansive urban space behind her. The open frame allows possibility, and it invites questions about Marnie and Charlie’s reunion. As the episode progresses, the vertical lines that trapped her early in the episode give way to open spaces where she and Charlie are the central figures in the image–fitting for an episode that is a self-contained love story.

The director of this episode, Richard Shephard, is the same director as “One Man’s Trash,” showing the strength of the collaboration between Dunham as writer and Shephard behind the camera. Whereas “One Man’s Trash” is an introspection of a minimalist, upper class aesthetic, in “The Panic in Central Park,” Shephard captures the turmoil of a failing relationship and balances that with capturing how the architecture of the city is malleable—providing the perfect backdrop for whimsical love affairs and harsh realities.

In the cinematography and mise en scène of its self-contained episodes, Girls has taken creative risks. Visually, these episodes demonstrate the trademarks of so-called “quality” television – single camera shooting (so, not the stage-y Friends multi-cam format), high production value, narrative complexity requiring “think piece” analysis, blurred lines between genres (think Louie’s comedy/drama mix), and difficult subject matter you rarely see “on television.”

But as easy as it is to categorize the show as one of many televisual products that uses middle-brow art techniques to validate itself, because Girls itself is about art and artist, these episodes become a way for Dunham and her collaborators to interrogate the marriage between form and style. By creating visually stimulating narratives about intimacy, love, and friendship, Dunham shows how these areas of life are as complex, and as worthy of artistic representation, as war, politics, and even death.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.