Dystopias are for Girls: Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan

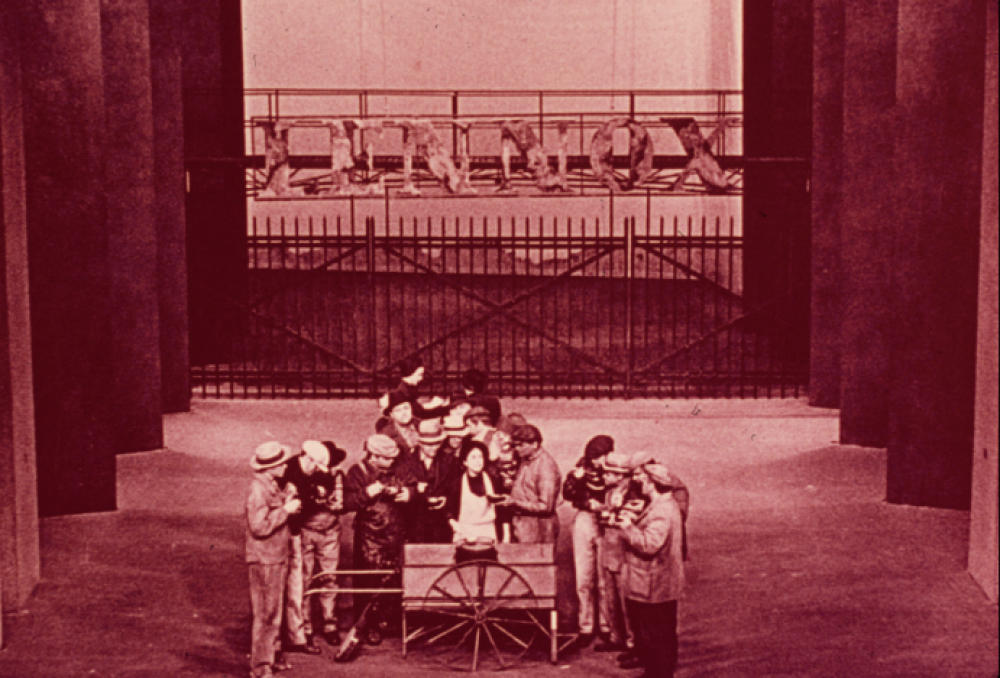

Still from The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Image via Open Culture.

“So this is a queer story?” I ventured to my husband as we watched Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc together. French comedy actress Renee Falconetti, in her only cinematic role, her face aflame long before she is burned at the stake, is entrancing. She defies categorization as male or female, young or old, ugly or beautiful, plagued by madness or the only one who knows the truth. The whites of her eyes, it seems, fill every frame; they overwhelm the viewer with their anguish, their unseen object(s) of absolute devotion. Her hair is closely shorn, the angles and lighting purposely unflattering: “In order to give the truth, I dispensed with ‘beautification,’” wrote Dreyer of his directorial choice.[1]

“Or it’s about gender? Feminism?” I questioned, later (there’s a lot of time to talk during a silent film, I discovered). “Or fascism?” We couldn’t ever reach a consensus.

As I watched, I wanted her story to be my own, somehow—for this Joan to be my Joan, or at least applicable to contemporary discourse (about women, bodies, faith, discipline, punishment, government: take your pick). I was grasping at potential narrative arcs, probably making some up along the way, making threads into through lines.

I’m not alone in my solipsism. The story of Joan of Arc, the 15th-century gender-bending teen canonized as a Roman Catholic saint in 1920, who led French soldiers into battle against the English during the Hundred Years’ War despite no prior military experience, has been reinterpreted in every era, and to suit every philosophy. In different cultural settings and representations, Joan has been portrayed (and hailed, and feared) as heretic, witch, martyr, warrior, mystic, and saint. She’s been, by turns, a champion of French nationalism, a socialist hero (as in Bertolt Brecht’s St. Joan of the Stockyards), and a mentally ill young woman, perhaps suffering from schizophrenia (after the advent of the field of psychology). In more contemporary iterations of her story, she’s been narrativized as a queer icon and protofeminist pioneer.

Joan of Arc has always inspired the kind of twin responses of fascination and censorship that often follow narratives with girls at the helm. T.A. Kinsey writes of the Dreyer film, “In its first year of existence, the film was censored, lost in a fire, recreated from unused footage, and burned again. The controversy surrounding this piece continues, fueled by the 1981 discovery (in a Norwegian mental hospital) of what appears to be a copy of the original negative.”[2] French censors considered the scenes involving the Catholic sacraments to be blasphemous; others were outraged by a scene that showed a baby nursing at a bare breast. Other representations, too, have garnered pushback and courted scandal.

Moreover, while Joan has been seen as a heroine for many different ideologies and movements, the level to which her resistance rose has been defanged by many interpretations. Cinematic retellings of Joan’s story, for example, “often deliberately excise the potential for female heroism that is evident in the medieval source material,”[3] claims reviewer Anke Bernau in The Sixteenth Century Journal, writing about Margaret Joan’s Portrayals of Joan of Arc in Film: From Historical Joan to Her Mythological Daughters. “As a result,” she concludes, “the twentieth-century ‘Joans’ have been shorn of anything radical or unsettling.”[4] In The Radicalization of Joan of Arc Before and After the French Revolution, Dennis Sexsmith goes further, arguing that Joan’s radical actions as both warrior and gender-bender have frequently been reclaimed and deployed by far-right extremists as propaganda for their own causes: “Political activists on the far right…adopted her as the model of the France they demanded: Christian, militarist, racially ‘pure,’ and, ironically given Joan’s exploits, socially traditional in terms of the roles of women.”[5] Behind most of these Joans, then, are male creators, making her into a text that serves one ideology or another.

This kind of narrative sterilization is not an infrequent response to stories about girl-heroes, who prove both eternally enticing and baffling. Onto the bodies and minds of girls, we often map projections of cultural anxieties, with the figure of the girl serving as both a repository for cultural moments and the consummate propeller of propaganda.

1968 production of Bertolt Brecht’s St. Joan of the Stockyards by the Berliner Ensemble. Image via Hekman Digital Archive.

The figure of the girl inspires both collective desire and collective anxiety. Rosalind Sibielski, in “Becoming Victim, Becoming Empowered, Becoming Girl: Discourses of Girlhood in the U.S. at the Turn of the Millennium,” claims that this leaves only two possibilities for girls and their media representations. These limiting possibilities are victimhood (“a narrative of girlhood in which the story of becoming girl is a story of becoming either a victim or a potential victim”), also known as girl-problem discourse (Reviving Ophelia is its canonical text), or neoliberalist empowerment, known as girl-power discourse (the Spice Girls and other kinds of riot grrrl-lite; diluted resistance).[6] In our fundamental distrust of girls, and our desire to pin them down like unwilling butterflies, we disarm their wings for the purposes of categorization and one-placedness. After all, girls are considered especially shifty, evasive, and especially nerve-wracking when they resist.

French feminist collective Tiqqun warned readers about “girl power” discourse and the neoliberalist postfeminist icon in their 1999 “Raw Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl.”[7] The figure of the Young-Girl, Tiqqun argues, is mined for her “raw materials” and fashioned into whatever the culture needs at the time: vulnerable victim, sex symbol, beauty standard, siren, red flag, consummate consumer, advertising image, or romantic object. Her image is used for its cultural currency, but she herself has no currency of her own. Indeed, Nina Power argues in Radical Philosophy: “Behind every Young-Girl’s arse hides a bunch of rich white men.”[8] So is the case, it appears, for many historical Joans.

Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan, an ecofeminist science fiction dystopian novel and the most recent retelling of Joan’s persistently relevant story, explodes all of these possibilities, finally allowing Joan the room to breathe (albeit polluted air). The year is 2049; a “geocatastrophe” has left nothing of Earth, and nothing of humanity, save a cluster of de-sexed survivors who make their uneasy home on a high-tech space station called CIEL, headed by Trump-esque celebrity dictator Jean de Men. Foucauldian disciplinary power has been literalized in CIEL’s central control, enforced by the Panopticon. People express themselves by fashionable skin grafts: the branding of narratives onto the body, literal skinstories that remain the only available connection to carnality, to flesh.

![]() Joan—of Dirt, this time—is Earth’s sole survivor, along with her soulmate, fellow rebel Leone. Since the age of ten, Joan has been directed (and tortured, and aided) by a blue light in her head that allows her to prophesize and connects her directly to the Earth, lending her the ability to harness both Earth’s creative and destructive forces as only a girl (rather than a Mother Earth) could do.

Joan—of Dirt, this time—is Earth’s sole survivor, along with her soulmate, fellow rebel Leone. Since the age of ten, Joan has been directed (and tortured, and aided) by a blue light in her head that allows her to prophesize and connects her directly to the Earth, lending her the ability to harness both Earth’s creative and destructive forces as only a girl (rather than a Mother Earth) could do.

Also central to Joan’s story, and necessary for its telling, is survivor Christine Pizan, who, at 49, is set to be euthanized by age 50 like all other CIEL citizens. Christine is fashioned after protofeminist writer Christine de Pisan, the sole chronicler of Joan of Arc’s revolutionary actions during her lifetime. Christine’s initial poem about Joan of Arc was, according to historian Anne Llellewyn Barstow, “the first of many literary attempts to encompass in one image of Joan both the masculine, invincible warrior and the diminutive but potent young maid,”[9] recognizing not only her power as a female military leader but her revolutionary potential as a girl of only sixteen.

Throughout The Book of Joan, Yuknavitch pays homage to the power of a girlhood (and the many ways a girlhood can be stolen, interrupted). Christine, an expert skin-grafter, is haunted by Joan of Dirt’s story, which she has branded into her own skin: “That story, of a girl-warrior killed on the cusp of her womanhood, and what happened after—it tilted the world on its axis, didn’t it?”[10]

In this imagined cyborg hub that is all that’s left of Earth, Joan’s story, like that of many other girls, has been rewritten to suit cultural purposes. The (false) story of her death-by-burning—which has been proliferated ad nauseum by the media—consumes anything she ever did, just as media narratives about girls’ vulnerability and destruction tend to overwhelm and overshadow girls’ narratives about themselves. Today’s breathless headlines lament girl culture, which is associated with the dark triad of sexting, selfies, and self-harm, conflating overuse of social media with externalized psychic pain, and implying that all of them originate from some kind of narcissism inherent to the girl, that forever misunderstood figure. Christine doesn’t share her contemporaries’ fascination. It is not Joan’s death that Christine writes on her body: It is her girlhood.

Yuknavitch’s approach to girlhood reaches beyond gender, and binaries in general: Both Leone and Joan are not clearly feminine, and even lean towards masculine at times, seemingly occupying a nonbinary gendered category. But Yuknavitch never strays from the lasting power of girl. She evokes the word like an incantation, lifting it out of and beyond the burden of its gendered, culturally laden constraints. Girl, here, is a possibility, a chance of becoming: At one point, a boy tells her about a girl who turns into song; Leone, her girl counterpart, will become not a woman, but a warrior, suggesting that there are paths for girls besides those to womanhood. “Girl,” here, is not a category of gender and age, but a blue light in a dystopian future that can level the earth, and so save it.

Yuknavitch’s Joan, moreover, does not indulge in positioning girls and women against one another. Christine, the fervent storyteller, requires the “raw materials” of Joan’s life to craft her skinstories, and Joan, who represents carnality (living, as she does, entirely bodily, and rarely speaking), requires Christine to be made legible, and for her resistance to acquire meaning. They grow towards and lean into each other, rather than Joan growing into woman or Christine the woman forgetting or distancing herself from her girlhood.

In another move that pushes against the illusion of binaries, Jean de Men is ultimately revealed to be not a man, but a woman who denies girlhood. S/he is the embodiment, not of manhood, but of toxic masculinity. Patriarchal narratives, here, are divorced from men; gender, in Yuknavitch’s imaginings, is irrelevant, save for its erotic potential. Patriarchal narratives, instead, are odes to representation and denials of the real.

In the Los Angeles Review of Books, Anne Jamison bolsters this assertion by positing signification-without-signifiers as the true object of distrust and vilification in this Joan retelling: “Poststructuralist theory — with its suspicion of narrative, of the possibility of direct access to matter, its belief in the primacy of representation, of signification over signified—might easily be read as the villain of this story, with cynical Jean de Me(u)n as its theoretical forebear/descendent.”[11] Indeed, Jean, like Him in Darren Aronofsky’s mother!, is presented as the author of a text akin to the Bible, consumed by the masses and critiqued by rebel-skeptics like Christine: “He wrote what was considered the most famous CIEL narrative graft of all time. Which somehow became hailed, by consensus, as the greatest text of all time.”[12] If the masculine God is text, then what is Joan, the girl? And what are her scriptures?

One answer is that, while Yuknavitch’s Joan pushes back against the god of text, it nevertheless elevates narrative. (And if we can’t imagine narrative without text, Yuknavitch suggests, that is the very problem.) Yuknavitch, and Joan, associate both the God-myth and tyranny with the worship of representation, of language divorced from the body, of sentimentality without sex and story without climax. Myth without purpose. Creation without destruction, and worship without obligation or responsibility. Signified without signifier, and vice versa. Reproduction without pleasure or oneness, as is Jean de Men’s ultimate goal, and how Christ, the story goes, was conceived.

Gilt bronze statue of Joan of Arc at the Place des Pyramides, Paris (Emmanuel Frémiet, 1899). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Though she explodes binaries wholesale, bringing life and death together in an unholy union, Joan and others argue for the power of narrative, pushing back against the diffusiveness of poststructuralism, insisting that story matters and so does the body. Through Joan’s girlhood-on-flesh, Cixousian “feminine writing” comes alive and is made literal. This isn’t merely pushback against phallogocentrism—women controlling the narrative—but something queerer, and messier. It stands to reason, then, that a girl is at its center.

Joan’s falsified death, Christine claims, is “the death that gave us life.”[13] In other words, this is a little-C christ story; Joan is juxtaposed, not with witches, warriors, or other religious folks, but with the dismissal of the power of the body, of girl (not to be confused with “girl power”). She is not a Messiah-worshipper, or the ideal follower, but rather the leader of her own cult, the cult of the body, the cult of the flesh made word. Joan of Dirt is already dust, never having felt the need to move beyond it.

Yuknavitch’s text overthrows the religious interpretations to which previous Joans have been beholden and instead explores the cult of the girl. What if “girls” and girlhoods were no longer false idols—magazine covers, sex symbols, and mannequins—but true deities, as Christine suggests? “The Bible and the Talmud, the Qu’ran and the Bhagavad Gita, the scrolls of Confucius and Purvas and Vedas—all that is over, I understand now. In its place, we begin the Book of Joan. Our bodies holding its words.”[14]

In many ways, Yuknavitch’s Joan is the anti-Young-Girl: “The Young-Girl,” Tiqqun writes, “wants to be either desired lovelessly or loved desirelessly. In either case, her unhappiness is safe. The Young-Girl has love STORIES,”[15] rather than love itself. And certainly, there is love here, far beyond story. The realization of love in its rawest and most erotic, bone-marrowed form is the driving force behind both Christine’s and Joan’s actions. The term “raw materials” is key here: While binaries and normativity are eschewed in Yuknavitch’s dreamed-up world, absolutes are not; love is treated with a kind of reverence, though it doesn’t take the forms we expect. Christine’s beloved is Trinculo, her lifelong soulmate (who also happens to be gay, and not sexually available to her). Before they die, as they lived—together—Christine gives herself over to their union completely, in positively Hedwigian fashion: “She leans in, opens her mouth to his, and lets their souls merge.”[16]

Joan, for her part, is devoted to Leone in a way that will make you feel like you’ve never been loved—not really. Her love for Leone transcends representation, and remains mostly unspoken in worldly life, as Joan rarely speaks: “Leone represented Leone, just Leone, Leone.”[17] She leaves behind a single material artifact, a letter, in which she tells Leone: “If there is such a thing as a soul, then you are mine.”[18] Leone, after sleeping atop Joan’s bones, consumes it in pieces, keeping Joan inside her as lovers long to do, but don’t, for any number of reasons. Joan’s salvation is, unsurprisingly, not conventional; she and her followers, save Leone, burn alive, but they burn alive together. All that will be left, her ending suggests, is our bones. And who will love them?

And though the journey ends in loss, Katharine Coldiron suggests in The Rumpus, it’s not Joan who loses, as she’s playing a different game altogether: “Joan does not participate in the binary. She does not play the patriarch’s game. In The Book of Joan, there is no man vs. nature—nature encompasses all. There is no man vs. man—men and women are extinct. There is no man vs. self—there is one woman, and a confounding shift in the paradigm of ‘life on earth.’”[19] Girl, in The Book of Joan, is some kind of dark freedom, a kind of boundlessness that can’t be reined in, a marriage of life and death that necessitates consummation. Girls, Yuknavitch argues, will not inherit the earth: they will destroy it so that it can begin anew again. Joan, like “girl,” embodies contradiction without collapsing: Joan is a messiah for those who don’t believe in them; binaries are exploded, but narratives with beginnings and endings remain lodged in the skin. The Book of Joan offers the possibility of the reclamation of narrative and bodies, and bodies-as-narrative; and perhaps, Yuknavitch suggests, girls are just the ones to do it.

[1] Carl Dreyer, “Realized Mysticism in The Passion of Joan of Arc.” The Criterion Collection (blog), November 08, 1999, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/69-realized-mysticism-in-the-passion-of-joan-of-arc

[2] Lisbeth Richter Larsen, “The Different Versions of ‘Jeanne d’Arc’,” Carl Th. Dreyer—The Man and His Work (blog). May 23, 2017, http://english.carlthdreyer.dk/Films/La-Passion-de-Jeanne-dArc/Articles/De-forskellige-versioner.aspx

[3] Anke Bernau, “Portrayals of Joan of Arc in Film: From Historical Joan to Her Mythological Daughters by Margaret Joan Maddox,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 40, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 1265-1266, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40023334

[4] Bernau, 1266

[5] Dennis Sexsmith, “The Radicalization of Joan of Arc Before and After the French Revolution.” RACAR: revue d’art canadienne/Canadian Art Review 12, no. 2 (1990): 125, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42630458

[6] Sibielski, Rosalind. “Becoming Victim, Becoming Empowered, Becoming Girl: Discourses of Girlhood in the U.S. at the Turn of the Millennium.” Rhizomes, no. 22 (2011), http://www.rhizomes.net/issue22/sibielski.html

[7] Tiqqun. Raw Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. 2010. Online translated version (original published as “Premiers Mat´eriaux pour une Th´eorie de la Jeune-Fille”in Tiqqun 1, 1999), https://libcom.org/files/jeune-fille.pdf

[8] Nina Power, “She’s Just Not That Into You.” Radical Philosophy, no. 177 (Jan/ Feb 2013), https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/reviews/individual-reviews/rp177-shes-just-not-that-into-you

[9] Anne Llewellyn Barstow, “Mystical Experience as a Feminist Weapon: Joan of Arc.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 13, no. 2 (Summer 1985): 26-29, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40003571

[10] Lidia Yuknavitch, The Book of Joan (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2017), loc. 265, Kindle.

[11] Anne Jamison, “Retrofuturist Feminism: Lidia Yuknavitch’s ‘The Book of Joan’” Los Angeles Review of Books, April 18, 2017, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/retrofuturist-feminism-lidia-yuknavitchs-book-of-joan/.

[12] Yuknavitch, loc. 167

[13] Yuknavitch, loc. 439

[14] Yuknavitch, loc. 1281

[15] Tiqqun, 4

[16] Yuknavitch, loc. 3113

[17] Yuknavitch, loc. 893

[18] Yuknavitch, loc. 3195

[19] Katharine Coldiron, “A Full-Throated Cry from a Clarion: Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan,” The Rumpus, May 01, 2017, http://therumpus.net/2017/05/a-full-throated-cry-from-a-clarion-lidia-yuknavitchs-the-book-of-joan/.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.