Cooking with Class: Food as Ornament

Roland Barthes, in his essay “Ornamental Cookery,” discusses the significance of recipes and cooking in French women’s magazines of the 1950s, noting they are proof “of the bourgeois domination of culture.”[1] Cooking, as represented in the texts he describes, are one way of creating myth, an “idea cookery” that proceeds to imagine and dream of garnishes and gentility, glazing over the price of food and other harsh realities such as economic class and gender norms. As Barthes puts it, “the real problem is not to have the idea of sticking cherries into a partridge, it is to have the partridge, that is to say, to pay for it.”[2] Barthes was writing about texts over fifty years ago, but there are striking similarities between the women’s magazines of Barthes’s analysis and the recently published book Date Night In.

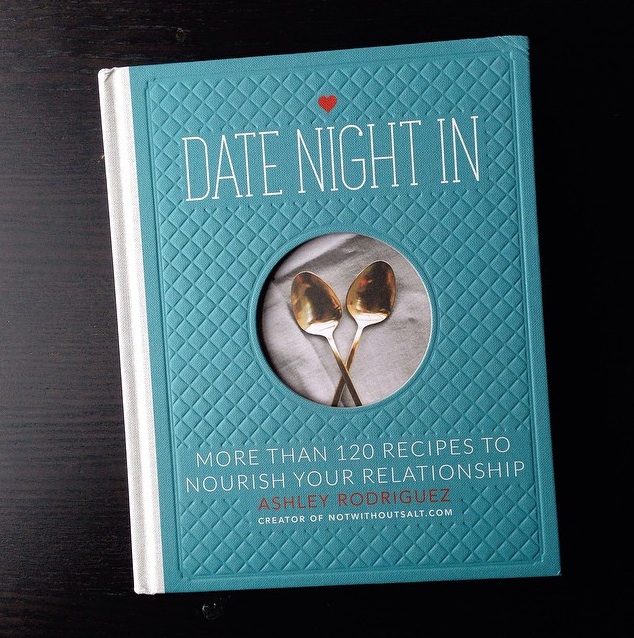

“Date Night In: More than 120 Recipes to Nourish Your Relationship” by Ashley Rodriguez was published late last year (December 2014) and is already in its second printing after the first edition sold out in approximately six months. Rodriguez, creator and writer of the blog “Not Without Salt,” was inspired to write this book based on her blog series entitled “Dating my Husband,” which features recipes and stories of weekly date nights with her husband. She writes, “these posts are often my most visited and commented on, and the subject of the most emails…I’ve had people tell me how they have renewed their relationships after reading these posts and starting the weekly traditions themselves.”[3]

With its quilted turquoise cover and red heart-dotted “i” in the title, this isn’t a cookbook in the traditional sense—a book that one can take into the kitchen and use. I would be scared to spill something on it, take notes, etc. The book is beautiful, to be sure. Hardbound with thick, matte pages and sharp photography (Rodriguez’s husband is a professional photographer), it feels more like a coffee table piece than cookbook. I should also note that many of these books are not defined as cookbooks. Rather than describing their publications as “cookbooks,” many food bloggers have written “memoirs with recipes”, books that are personal narratives with recipes capping each chapter.[4] The classically-defined genres of books become murky—as objects, what are these new books’s function? Are they instruction manuals, personal narratives, or usable cookbooks?

Rodriguez tells us in her introduction that she and her husband leave a space open, once a week, to “date.” She explains the book is meant to “invite the reader into our home as we fall deeper in love through great food” with the intention of keeping recipes simple and easy to make, with a timeline and very clear instructions on how to prepare for the date.[5] She describes to the reader how on the same day every week (usually on a Thursday), her husband puts the kids to bed and makes them both a cocktail while she prepares dinner.

A photo of the couple, Ashley and Gabe Rodriguez, in their Seattle kitchen. Photo by Boone Rodriguez. March 2014.

Like online food blogs, these books become a gateway to accessing another’s life. Rodriguez, a wife, mother, and cook, acts as the narrator, the teller of the story of her and her husband’s dating and married life. The book moves through her voice, which she uses to cut a template from which other women are able to emulate and re-create these date nights. Her emphasis on the ritual and ceremony is as fascinating as it is informative.

The repetition and need to perform the same movements to create a date is not only re-creating the memory of dates past for this couple. The ritual is complicated with gender, race, and class, and becomes further charged as a tool of hegemonic power when a book such as this one is created from it, to be used as a model for the reader’s home. Post-colonial theorist Homi K. Bhaba examines how colonialism, power, and control are activated in current culture. He states that “ when authority does not conceal itself, but is repeated in text, a space where resistance or subversion may be enacted is created.”[6]

Are texts such as Rodriguez’s a pattern to repeat a capitalist and bourgeois culture dominated by white patriarchy? In Date Night In, the authority that reveals itself is that of whiteness and embodied, enacted heteronormative gender roles. It may seem that a cookbook is a simple object, but Date Night In works (just like the women’s magazines Barthes wrote about) to reify dominant culture. As Arjun Appadurai writes: “While it may not be clear how individual cookbooks are actually utilized, the ideals they project reveal much about their historical and cultural context.”[7]

I am curious to explore these themes through a series that investigates how cookbooks, recipes, and food transmit culture and memory. As an unmarried woman of color on the lower end of the socio-economic scale, what happens as I repeat and perform this particular ritual? How am I activating this text by following this book, investigating its details and ornaments?

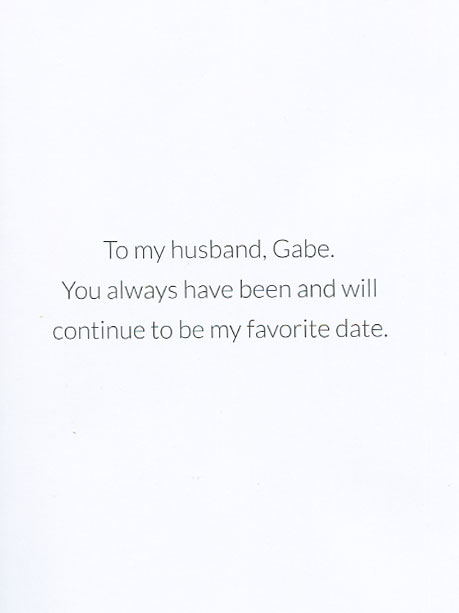

Practically speaking, though, I worry I am insane to try this little experiment I’ve conjured up for myself. On top of making meals for my partner and I in addition to a meal chewable by a small child with few teeth and a dairy allergy, I would be making romantic recipes to “nourish my relationship.” And to say my partner is wary is an understatement, as his thoughts on the book are less than positive—I’ve never seen a more dramatic eye-roll than his as he read the colophon.[8]

Yet I plan to examine this mythical object (as Barthes would put it), taking a peek into what it unwittingly reveals about the state of our culture today. I want to attempt to clarify how we utilize an individual’s story and how it becomes a tool of power and authority. Homi K. Bhaba writes, “to repeat authority is to destabilize that authority.”[9] Bhaba’s exploration of how colonial power is rooted in difference and repetition is at the heart of this experiment. By recreating and repeating Rodriguez’s directions, I investigate how the identity of the individual performing this ritual can subvert it.

With all this in mind, here is what I propose: I will do my best to recreate a menu per week for the coming weeks, as close to the instructions and recipes as possible, in an attempt to discover what is at the core of this cookbook. I will travel this culinary misadventure with academic theory, the unabashed enthusiasm of Rebecca Harrington and a dilettante’s “healthy dose of snark.” I’ll be back with what I find.

[1] Barthes, Roland, 1957. Mythologies. New York: The Noonday Press. P. 79.

[2] ibid.

[3] Rodriguez, Ashley, 2014. Date Night In: More than 120 Recipes to Nourish Your Relationship. Philadelphia: Running Press Book Publishers. P. 9

[4] A few examples of this genre are Amelia Morris’ book Bon Appetempt, Luisa Weiss’ My Berlin Kitchen, and Molly Wizenberg’s two books, A Homemade Life and Delancey.

[5] ibid.

[6] Bhaba, Homi K., 1994. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge. P. 122

[7] Appadurai, Arjun, 1998. “How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India.” Comparative Studies in Society and History Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan., 1988), pp. 3-24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. P. 22.

[8] “To my husband, Gabe. You always have been and will continue to be my favorite date.”

[9] Bhaba, Homi K., 1994. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, P. 93

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.