It’s in the Cloud: Miasma, Healthcare.gov, and Computing

The connection to our health and our healthcare is seemingly invisible: the digital marketplace, eco-friendly billing, paperless records. All of this lives in “the cloud,” existing just out of sight. As a digital stratosphere hosting our more personal information, the cloud mysteriously permeates our daily lives, especially in regards to our health. It hosts the online health insurance marketplace—the current but maybe-going-away-soon digital scape where we shop for a plan to care of our living bodies. It’s also the home of the GoFundMe campaigns through which we digitally transfer funds to those whom the health insurance marketplace have failed. We use email to correspond with our doctors and our health insurance companies, and apps to track our heart rates and exercise regimens, seeding the cloud with our data points. The cloud is omnipresent in our lives and critical to how we understand our bodies.

Clouds are a pervasive force in the history of healthcare. Prior to germ theory’s widespread acceptance in the late 19th century, the theory of miasma explained how illness and disease were spread. We can turn to the Encyclopedia of Public Health (edited by Wilhelm Kirch, the former President of the European Public Health Association) to explain what miasma is and how it worked.

In medieval times, and beyond, people assumed that diseases were caused by a pollution of the air, the so-called miasma. This theory was thought to explain why some regions were prone to mass diseases of their populations. As for therapy, treatment of the air was considered to be effective; fire or balmy essences were thought to cleanse the atmosphere.[1]

With noxious fumes and toxic hazes visible to the human eye and nose, it seemed plausible that such an unfortunate environment would have a negative impact on one’s health. It may not have been the scientific cause, but spread of the common cold through germs shared via sneeze or cough wasn’t too far off what was ultimately discovered at the end of the 19th century.

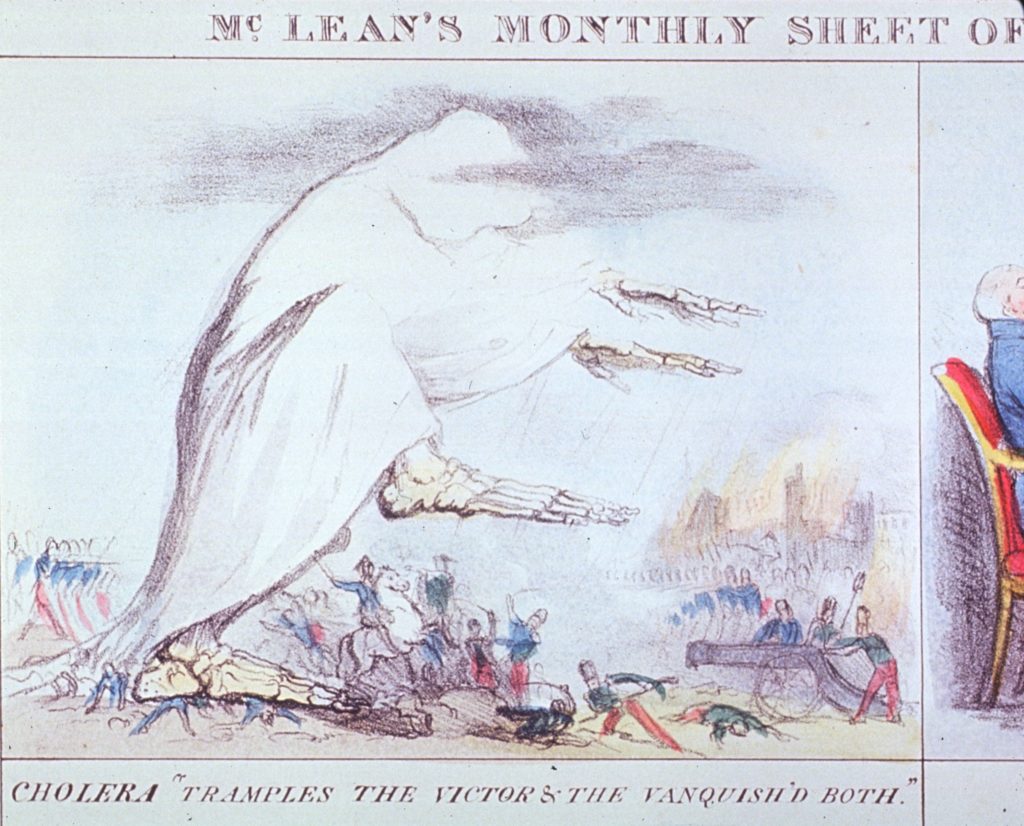

Robert Seymour, Cholera “Tramples the victors & the vanquished both.” October 1, 1831. Image via U.S. National Library of Medicine

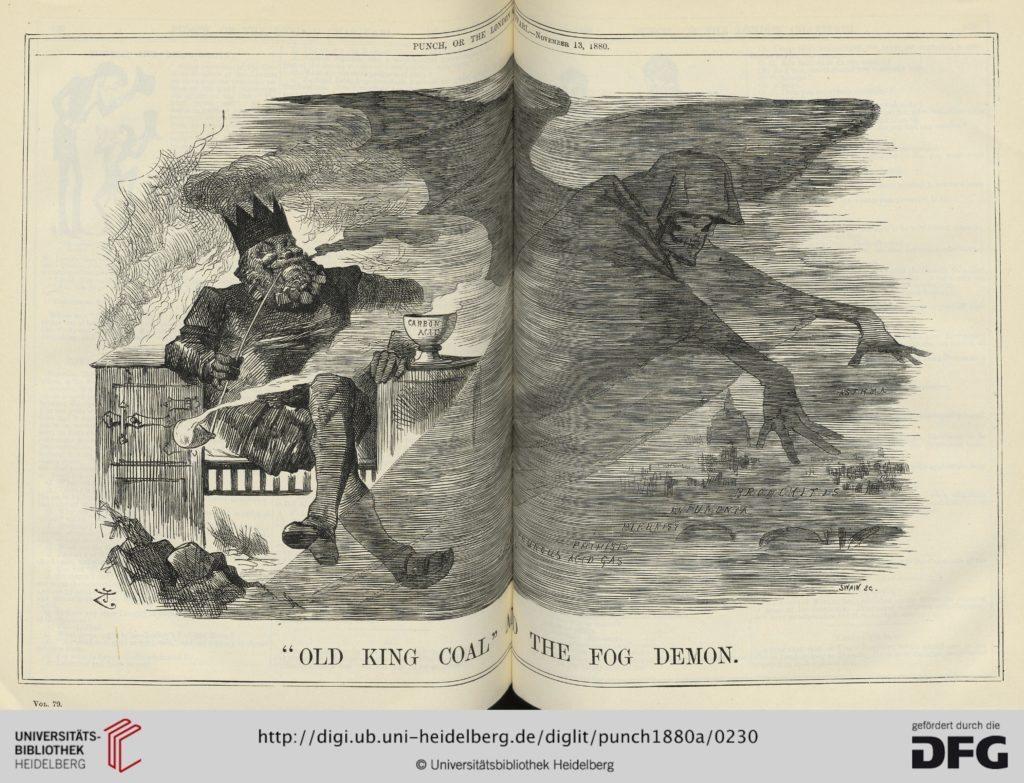

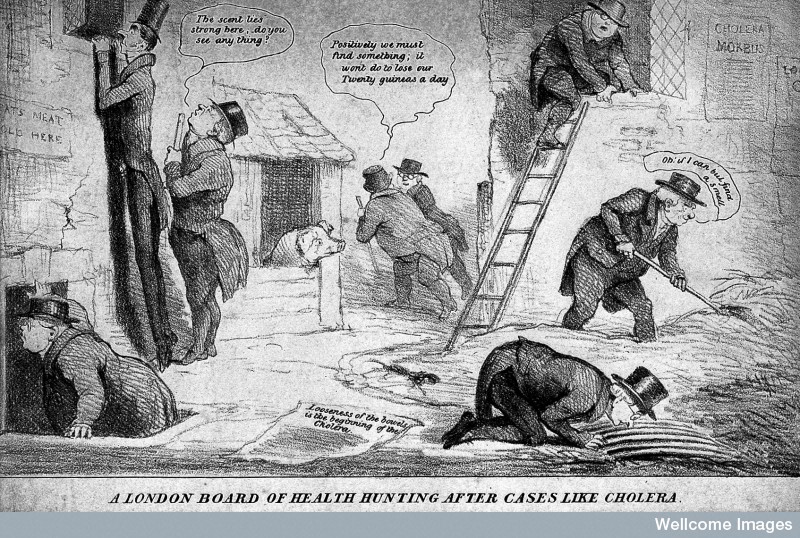

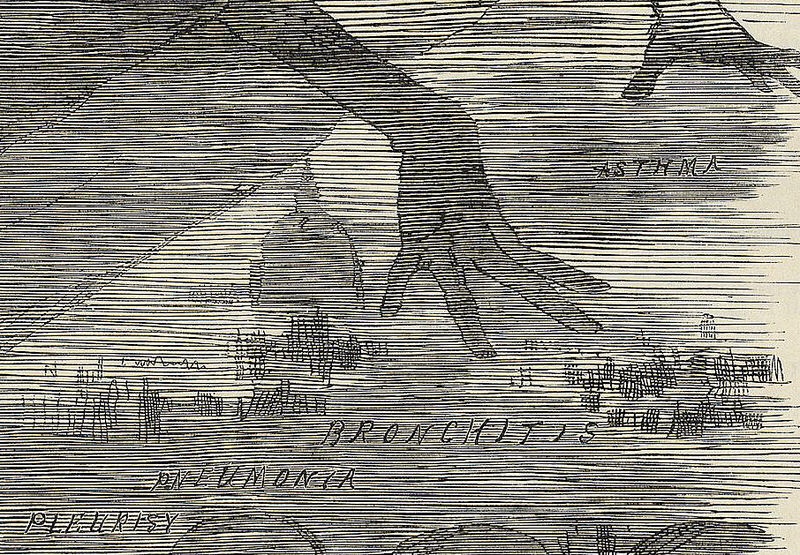

Miasma was illustrated as eerie gray clouds hanging over its eventual victims. This low-hanging diseased smog haunted many cities and towns across Europe and the United states. The stench of bodily waste, human refuse, and the pollution from industrial infiltrated the senses and anxieties of people trying not to get sick. If they could not afford to retreat to non-urban or less densely populated areas, they would likely become sick. For those that were stuck in urban centers surrounded by soot and waste, unable to afford a retreat into fresh rural air, illness was inevitable.

”Old king Coal” and the Fog Demon’, a cartoon featured in Punch, November 1880. Image via Universität Heidelberg.

At the start of the American Civil War in 1861, miasma was still the leading theory on how people became sick. While it’s obvious that much of the suffering on the battlefield was related to cannonballs and single-shot rifles, there were other concerns beyond the cloud that hung over the Civil War landscape. The battlefields were full of decaying bodies, killed by violent warfare and the diseases that ran rampant across field hospitals. The stench of the battlefield was rancid. Mark M. Smith, a sensory historian of the Civil War, quotes volunteer nurse Cornelia Hancock on the air of the battlefield:

Not the presence of the dead bodies themselves, swollen and disfigured as they were and lying in heaps on every side was as awful to the spectator as that deadly, nauseating atmosphere which robbed the battlefield of its glory the survivors of their victory and the wounded of what little chance was left to them.[2]

Cornelia Hancock describes the atmosphere as so putrid that it may go on to kill those that survived battle. If it wasn’t the miasma hanging over combat zone, it was the high number of amputations and wounds that were tended to by medical professionals with dirty hands and unclean bandages. Despite their best intentions, doctors moved from one infected wound to the next; a mass mixing pool of disease and germs spread from person to person. Bodies decayed in open fields, creating a rank stench that haunted the living. Despite this grotesque scene, it wasn’t the air that was killing them, it was the other invisible soldier: germs.

“A London Board of Health hunting after cases like a cholera.” Published in The Looking Glass or Comical Journal, 1832. Image via Wellcome Images.

Germ theory and its various implications for sanitation, however, had not been popularly accepted in time for them to make a positive impact on the medical care in the Civil War. In the early 1860s, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch were still working to complete their scientific experiments and research. Pasteur and Koch had begun in the 1850s, but did not make any significant headway until the early 1860s when Pasteur developed bacterial growths in broth. When heat was applied and no fresh air was exposed to the liquid, the bacterial growth halted. Inversely, when heat was applied and the top of the flask was exposed to air, the bacteria grew. This was the first step to understanding pasteurization as we currently know it and also key to eradicating the theory of miasma and the myth of bad air.

Miasma finally shifted out of the cultural norms of the era at the end of the 19th century with the discovery of viruses in 1892. [3] Medicine looked brightly forward to a fresh and clean start of the 20th century. The cloud of miasma no longer haunted their patients. It was now germs and microbes, seen and researchable, that would plague us, but the cloud no longer threatened illness.

Fast-forwarding to 2017, we have a decent idea of how germs work, where they go, and how our bodies respond. The field of medicine is vast, exploratory, and generally well-trusted. Our relationships to our bodies are mediated through our doctors, our family histories, and how we gain care. This part is where it gets sticky, though. More often than not, if we’re lucky enough to have health insurance, much of this process is not only confusing but seemingly invisible. It is another version of the cloud. The 21st century cloud, however, is vastly different than the miasma cloud that hung over dank, overpopulated regions with bad air.

The cloud is understood by everyday users as some kind of pseudo-invisible data storage, accessible from our smart phones, laptops, TVs, and anything else that can be connected to WiFi. Data farms, or “cloud campuses,” comprised of huge storage warehouses, filled to the brim with servers to hold the precious information that we rely on accessing every day. This includes everything from the multiple cat photographs we took and needlessly backed up to the many bad Beatles tribute homepages we made as kids in the 90s. These casual files co-mingle with all of your most precious medical information, from the blood levels in your annual checkup to the dirty details of the urinalysis you got when you already knew you had a UTI. All of this is hanging out in the cloud, which is not a cloud at all but a very real space. The cloud connects bodies, platforms, and information through technology that we imagine as invisible.

The cloud’s seeming invisibility, at first pass, seems rooted in nature. The very nature of clouds is often somewhat removed from sight, an omnipresent feature of the outdoor world, which we are often separated from by both roofs and layers of atmosphere. In many ways, clouds border on the magical: home of the heavens, thunder, tornadoes, and rainbows. Our distance from them makes them seem almost otherworldly. It seems inevitable that the digital cloud would be made up in a similar way: removed but ubiquitous, powerful but quiet. When it comes down to it, the specific details of digital storage may simply be too complicated for the layperson who is just going with the cultural flow. It may also be a clever marketing campaign for a system that requires your trust—after all, the cloud holds your most intimate details even though you have no idea how or where they’re stored.

In reality, the 21st-century cloud is still made up of stuff: radio waves, fiber optic cables, routers, and fans, all built from valuable resources and powered by electricity. These high-tech server farms are built as cheaply as possible, often in remote areas where companies can afford to buy a lot of land and supply a lot of electricity. Housed in large, anonymous buildings away from populations of people, they are nearly invisible to most people. The aesthetic of data is the mundane.

Cables outside a data center. Image by Ingrid Burrington via The Atlantic.

The carbon footprint of data is surprisingly large for something we don’t often see. In 2011, Greenpeace released its findings from its “How dirty is your data?” study, which was a large scale investigation on the environmental impact of energy resources in cloud computing. Greenpeace hoped to shed light on what is otherwise a fairly secretive industry, drawing attention to its energy use.

-

Data centres to house the explosion of virtual information currently consume 1.5-2% of all global electricity; this is growing at a rate of 12% a year.

-

The IT industry points to cloud computing as the new, green model for our IT infrastructure needs, but few companies provide data that would allow us to objectively evaluate these claims.

-

The technologies of the 21st century are still largely powered by the dirty coal power of the past, with over half of the companies rated herein relying.[4]

In the last six years, there has been more investigation into how data storage is powered, and what materials are required in order to make the whole system work. However, there is still no agreed upon metrics on how much electricity is required to keep these data farms running, and kept at a cool, constant, powered state. If you were lucky enough to invest in a computer in the 1990s with a tower, you’ll remember the whir of the fan after hours of use, and how hot it became. Imagine that, but extrapolated to the utmost degree: towers stacked on towers of hard drives, constantly powered and running, with giant fans to cool them. The usage is immense and more noticeable than the cloud itself.

Image via healthcare.gov

Image via knowyourmeme.com

While “the cloud” does connect us to our bodies with tangible data, it also obfuscates a sense of ownership over our care and our health trajectories. It can be challenging to make sense of the bodies we inhabit and connect to the care we need when all of it is mediated through digital transactions, whether that be the vast landscape of the healthcare marketplace or the anxiety of opening an email with troubling blood test results. We have all of this information at our fingertips, yet we often lack the tools to make sense of the data we have. The cloud is a receptacle for this, but is not an effective interpreter. Technology expands our identities into virtual space less effectively when we lack an understanding of it.

Ultimately, the cloud has been and continues to be a techno-cultural space of translation for how we imagine our health and our health care. It is a space for us to make sense of how we understand our bodies. In its change from miasma to data storage, the cloud’s continual presence in our cultural imagination serves as a reminder that we rely on common metaphors that aid understanding in imperfect ways. Miasma visualized a literal cloud: a shifting pollutant shape taking over and ending the lives of the unlucky and disparate. The digital cloud as we now know it is equally omnipresent and perhaps equally leaky, a shifting space to hold our imagination and our bodily futures.

[1] Kirch, Wilhelm. Encyclopedia of public health. London: Springer, 2008. 762.

[2] Smith, Mark M. The Smell of Battle, The Taste of Siege: A Sensory History of the Civil War. New York: Oxford, 2015. 79.

[3] “The Discovery of Viruses.” Science and Its Times, edited by Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer, vol. 5, Gale, 2001. Science in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CV2643450476/SCIC?u=la99595&xid=90ed7c42. Accessed 16 Oct. 2017.

[4] Cook, G. & Van Horn, J. How Dirty is your Data? A Look at the Energy Choices that Power Cloud Computing. Greenpeace International, 2011. http://www.greenpeace.org/international/Global/international/publications/climate/2011/Cool%20IT/dirty-data-report-greenpeace.pdf

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.