AHS: My Roanoke Nightmare and our Incoherent Understanding of Trump Voters

Colonist John White discovers the word “Croatoan” carved on a post in the abandoned Roanoke settlement. Artist unknown, image via Wikimedia Commons

In the especially gruesome fifth episode of American Horror Story: My Roanoke Nightmare, a character pleads with the flesh-eating Polk family to release her, promising, “We will go back to California. No one will ever see us again.” It’s a sentiment heard from many West Coast Democrats after November 2016, though no one threatened to make “sweet meat” of them.[1]

The AHS anthology series has always been socially engaged, if in somewhat bizarre ways. Always queer in its sensibilities, the show has been celebrated as feminist for its embrace of aging divas, giving actresses such as Kathy Bates, Angela Bassett, and Jessica Lange juicy roles and plenty of screen time. Across its seasons, AHS has been sort of generically political, taking on topics such as the treatment of gays and lesbians as pathological (in the Asylum season), domestic abuse (in the opening haunted house season), and the othering of cultural outsiders (in season four’s freak show setting). But with the spinoff American Crime Story taking on the O.J. Simpson case—a venture that garnered wide acclaim as well as Emmy and Golden Globe awards—the franchise has dialed in to more historically specific cultural engagements.

This more particular engagement with American culture took a contemporary turn when show creator Ryan Murphy announced that the next season of American Horror Story will focus on the 2016 presidential election, a statement he later corrected to say that it might be an allegory, as all seasons are.[2] Although this announcement is sure to elicit a few bitter chuckles amongst those Americans who’ve taken to describing Trump’s America as a horror show, it’s not totally surprising.

In his most recent season, My Roanoke Nightmare, Murphy engaged (albeit obliquely) the culture wars that led up to the election. In this season, which aired throughout Fall 2016, Murphy updated the ghostly early American mystery of a disappearing colony to explore the rifts in present-day American culture. The Roanoke season fits most explicitly with Murphy’s interest in old American fears (Voodoo, witches, vengeful Puritans, and other horrors), but by pitting stereotypical rural hillbillies against equally stereotyped coastal elites (complete with yoga and gluten allergies), Murphy also previewed the strength of cultural divisions that would blindside so many American voters and pollsters in November 2016.

There’s a messiness to the story arcs of most seasons of American Horror Story that makes it a perfect document for tracing our sometimes incoherent ways of parsing a divided nation. Watching pundits attempt to explain what happened when Americans went to the polls in November, I’ve been frustrated by a kind of intellectual and explanatory stuttering. There’s been a popular narrative about the Trump voter: the forgotten poor white man in rural America raging at the neglect of and disrespect shown to his culture. The election that launched a thousand think pieces has included those which plead for understanding, a plea that has pushed books such as J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy onto bestseller lists and podcasts like S-Town to the top of charts. On the other side, recent essays viciously excoriate rural whites for a stubborn idiocy that means sticking to impoverished and backwards ways of living despite a nation moving in other directions. Such lashings have often come from conservative never-Trumpers, such as the National Review’s Kevin Williamson and David French, the latter writing of rural whites: “If getting a job means renting a U-Haul, rent the U-Haul. You have nothing to lose but your government check.”[3]

Such pieces are strangely tenacious given certain demographic realities about the so-called Trump voter. As Clare Malone has recently noted on FiveThirtyEight, “The visual trope [of the Trump voter] is cling-wrapped to our brains: red hats, stadium crowds, rippling flags, chanting.”[4] Nonetheless, as Malone and others have to keep reminding those seeking yet another analysis of November, these aren’t the people who put Trump in office. 47% of voters this cycle were college-educated white people, and trump won 63% of this group.[5] That’s a lot of educated white people who voted alongside the more stereotyped image of the Trump voter.

The thing is, though, that the educated Americans who author such think pieces, like many Americans who have come before, like to place the enemy at the geographical fringes.

This spring, I taught a college class on the “American Experience,” positioning the Roanoke series alongside the early American captivity narrative of Mary Rowlandson, who likewise located horror in the wilderness. Initially, I meant the pairing to help students understand how far back certain ideas about wilderness and civilization go. With Rowlandson, we see an Englishwoman, a Puritan, taken captive during King Philip’s War. She describes her captors as part of an evil very much tied to the landscape they inhabit:

I went along that day mourning and lamenting, leaving farther my own Countrey, and traveling into the vast and howling Wilderness; and I understood something of Lot’s Wife’s Temptation, when she looked back…When I came to the brow of the hill, that looked toward the Swamp, I thought we had been come to a great Indian Town (though there were none but our own company). The Indians were as thick as the Trees: it seemed as if there had been a thousand Hatchets going at once. If one looked before one there was nothing but Indians, and behind one, nothing but Indians; and so on either hand; I myself in the midst, and no Christian Soul near me.[6]

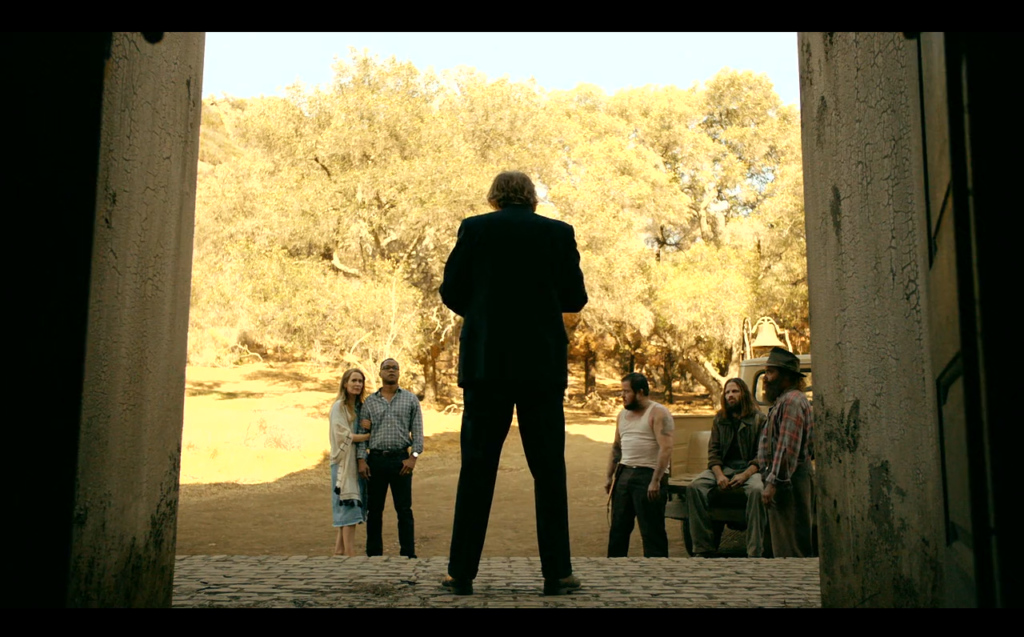

In a vein not so very different, the AHS season opens with an interracial couple moving from Los Angeles to rural North Carolina to start a new life in a neglected home that borrows its architecture from The Amityville Horror. When bidding for the house at auction, the couple, Shelby and Matt, find themselves putting money up against the local Polk family, who go back generations in that area. The scary-looking Polks wear trucker hats and have bad teeth and skin, those classic markers of class status. In contrast, Matt is a young black professional, jumpy at the possibility of police prejudice, and Shelby is a white woman who “works” at practicing yoga and drinking wine, primarily. The obvious enmity between the two groups becomes triangulated as we learnt that this particular haunted house was built on the land where the English colony of Roanoke went missing, one hundred and fifteen settlers gone with little trace. American Horror Story fills in the details of this colonial mystery through the figure of Kathy Bates’s character The Butcher: the ghost of one of the colonists, who was a woman determined to make her people succeed in this new land at any cost. And, this series being what it is, the cost is particularly gruesome blood sacrifice.

Kathy Bates as “The Butcher” in Chapter 3 of AHS: My Roanoke Nightmare. Screen capture by the author.

As I edged up to ending my course unit with this pop culture example, I became increasing nervous about how my students might see the show’s deployment of rural stereotypes. Nevada, where I teach, is pretty much as divided between rural and urban as you can get, with something close to 90% of the population living in 10% of the state’s land.

Part of what’s tricky smart about Murphy and his series, though, is that he appears to hold no American in particular esteem, whether the rosé swilling interlopers or the human-jerky-eating hill people. Nonetheless, it’s true that the stereotypes tied to the rural Polk family are more extreme. For one, this clan eats people. For two, the Polks seem to further the family line primarily through incest. And third, the barn where the family grows marijuana (the least of their crimes) features a Confederate flag as its most notable décor.

But if these rural characters are thinly drawn, Murphy’s flat stereotypes allow him to explore something a bit darker in his more psychologized urban characters that should remind us of horror’s long tradition of riffing on those who live on “civilization’s” fringes: consider the mildly off-the-beaten-path Bates family in Psycho, left behind by modernity when the highway comes along, cutting the mother, son, and motel off from the rush of cars. Or, more extreme, the flesh-eating family of Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Or, in a more realist pallet, the Southern Gothic sadists of Deliverance. In all these cases, getting away from the road and the big city means bad things to come.

Layering contemporary culture wars atop a colonial backdrop is a particularly genius move on Murphy’s part, because it allows the show to remind audiences about the way in which claims to authenticity—who/where is the “real” America?—and ownership are centuries old. For example, among the creatures haunting the house, we have the ghosts of a Taiwanese immigrant family, the Chens, who came to America in the 1970s to start over, only to be pushed out by the ghosts of the earlier Puritan immigrants. And, reminding us of the distaste (no pun intended) many Americans had for poor Southerners during the Great Depression, the Polks claim that they are the “first family” of the region. This serves to justify their by-any-means-necessary survival strategies, as recounted in episode eight’s bastardized Scarlett O’ Hara performance by Jether Polk, who explains that having survived the Depression on people meat, he was “never gonna go hungry again.”[7]

Unfortunately, the Native Americans who may have killed off or absorbed the Roanoke colony do not make an appearance in the series’ rehearsal of various contests for land. But when Kathy Bates roars that she will “stop at nothing to hold safe this colony” and that she must protect it from “trespassers,” the long and bloody history of U.S. land claims resonates through her period dialect.[8]

Part of what the series stages so well is the simultaneous fascination with and horror of this contested piece of land. In the final episode, one of the last characters standing muses, “If those settlers didn’t want anybody bothering them, they shouldn’t have picked such a pretty place to make their home.”[9] But, the matter of who makes a home in rural America is precisely the issue. As scholar Bernice Murphy writes in The Rural Gothic in American Popular Culture, living at the edge of the woods has always signaled a kind of danger in the U.S. cultural imagination, a danger that could contaminate those who made their homes there.[10] Writing of Puritans (including Rowlandson), Murphy offers this schematic: “the forest beyond the settlement is the place where the representatives of ‘civilization’ are pitched against forces that embody ‘savagery,’ and order—moral, psychological, and geographical—is opposed to ‘chaos’” (16).

Such ideas traveled from the Puritan era to the Revolutionary age and beyond. In 1782, trying to explain the new nation across the Atlantic, French author Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur noted that it was where Americans were wildest—“There, remote from the power of example, and check of shame, many families exhibit the most hideous parts of our society”[11]—but he, like 1890s historian Frederick Jackson Turner after him, thought these rough Americans would eventually become civilized, working out their energies as culture spread. In 1893, a few years after census data declared the “closing” of the frontier, Turner proclaimed in his frontier thesis that Americans would have to expand elsewhere to release these unruly spirits, thus ushering in an age of empire.[12] In the contemporary figure of the “hillbilly” we see both the lingering sense that such Americans are the wild and wicked who choose to live away from cultural centers, but it is also evident that doing so in our present moment is a kind of perverse rejection of the civilization that has long since arrived—resulting in the presentation of these denizens as a kind of curdled, human spoilage by pundits such as David French. A friend of mine, a professor of Southern Literature, once described her students’ disgusted reactions to rural Southerners: “Who are they, why are they?”

To be fair, many truly disturbing horrors have marked America’s rural landscapes, and these are on view in American Horror Story as well: in the third episode, we learn the police are in cahoots with the Polk family; much use is made of mutilated pig corpses, recalling anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim hate crimes. Although the Polks won’t turn out to be directly responsible, one black man meets an end that cannot recall anything but the United States’s lynching history. It is, in short, a depiction of rural America as multi-cultural leftist nightmare, a leifmotif that the show repeats in a number of increasingly baroque and disturbing tableaus.

Through such a rehearsal of the worst abuses of immigrants, gay people, and African-Americans, Murphy has readied his audience for vengeance against the Polk family, who make people jerky and tell their coastal elite captives not to “act all biggety” as well as rehearsing such choice bits of wisdom as: “If you ain’t Polk, you ain’t people.”[13] The elites become as brutal as anyone, especially as the Polks come to fulfill the newcomers’ initial suspicions about them. While early on the coastal elite characters use language like “inbred” and “swamp people” to describe the Polks, by episode eight, the series has so ratcheted up the Polks’ abuses that the audience is rooting for the actress who bashes Mama Polk’s head in with a hammer.

Part of what Murphy’s series shows, though, and what seems true of our stubborn confusion about the Trump voter, is that Mama Polk isn’t the real story—or at least not all of it. The land is haunted, and she’s just one of the more easily hateable ghouls roaming the landscape. The stickiness of certain images of the Trump voter is due in part, I’d argue, to the convenience of locating the culturally or politically disagreeable at the geographical as well as economic or cultural fringes of society. It’s convenient both because it’s a habit some centuries in the making and because for some of us, it draws focus from the more banal sources of evil closer to home

The suburban women in Pennsylvania, the moderate Republicans who recoiled when faced with the name “Clinton” in the polling booth, the Bernie Bros who called a qualified politician the “lesser of two evils,” and the wealthy who just didn’t want to pay more taxes (like always) offer less pure villainy for the cultural elites who, when it gets right down to it, don’t know many uneducated rural people.

To be sure, Murphy’s political critiques are often imperfect. This season, like most, has a shift in the middle, this one become hyper-aware of our media moment, deploying meta-fictional strategies that go completely bonkers by the self-cannibalizing final episode in which the taping of a reunion show is crashed by wannabe YouTube celebrities. The YouTuber’s story is interrupted by a true crimes show, a Barbara-Walters-like special that calls back to an earlier season of AHS, a Bravo-ish behind-the-episode show, an online fan review, and so on. If this sounds exhausting, it is. But so is our current political scene.

[1] American Horror Story: My Roanoke Nightmare. “Chapter 5.” Episode 5. Directed by Nelson Cragg, written by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk (creators), and Akela Cooper. FX, October 12, 2016.

[2] Michael Schneider, “Ryan Murphy Says Don’t Take Him Literally; New ‘American Horror Story’ Won’t Feature Donald Trump,” Indiewire, February 24, 2017, http://www.indiewire.com/2017/02/ryan-murphy-american-horror-story-donald-trump-election-1201786746/

[3] David French, “Working-Class Whites Have Moral Responsibilities—In Defense of Kevin Williamson,” National Review, March 14, 2016, http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/432796/working-class-whites-have-moral-responsibilities-defense-kevin-williamson

[4] Clare Malone, “‘Reluctant’ Trump Voters Swung the Election. Here’s How They Think He’s Doing,” FiveThirtyEight, April 18, 201. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/reluctant-trump-voters-swung-the-election-heres-how-they-think-hes-doing/

[5] Harry Enton, “Registered Voters Who Stayed Home Probably Cost Clinton the Election,” FiveThirtyEight, January 5, 2017, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/registered-voters-who-stayed-home-probably-cost-clinton-the-election/

[6] Mary Rowlandson, A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, in Classic American Autobiographies, ed. William Andrews (New York: Signet Classics, 2014).

[7] American Horror Story: My Roanoke Nightmare. “Chapter 8.” Episode 8. Directed by Gwyneth Horder-Payton, written by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk (creators), and Todd Kubrack. FX, November 2, 2016.

[8] American Horror Story: My Roanoke Nightmare. “Chapter 3.” Episode 3. Directed by Jennifer Lynch, Written by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk (creators), and James Wong. FX, September 28, 2016.

[9] American Horror Story: My Roanoke Nightmare. “Chapter 10.” Episode 10. Directed by Bradley Buecker, written by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk. FX, November 16, 2016.

[10] Bernice Murphy, The Rural Gothic in American Popular Culture: Backwoods Horror and Terror in the Wilderness. New York: Palgrave, 2013.

[11] J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur. “What is an American?” in Letters of an American Farmer, originally published 1782. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/crev/contents.html

[12] Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in The Frontier in American History, originally published in 1921. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22994/22994-h/22994-h.htm#Page_1

[13] American Horror Story: My Roanoke Nightmare. “Chapter 8.” Episode 8. Directed by Gwyneth Horder-Payton, written by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk (creators), and Todd Kubrack. FX, November 2, 2016.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.