Success Sans Tragedy: the Story of Katy Perry

Read the favorable reviews of the following films and you will get a sense of how thoroughly the rock-doc, music biopic genre has been reinvigorated: Montage of Heck, Amy, What Happened Miss Simone?, and the Brian Wilson biopic Love & Mercy. All these films share tragic musical figures at the core. Tragic musical figures that made iconic and important music. But what does the rock doc look like when the figure at the center is neither a tormented artist nor an iconoclast? What if the artist at question is a pop star that people don’t even take seriously?

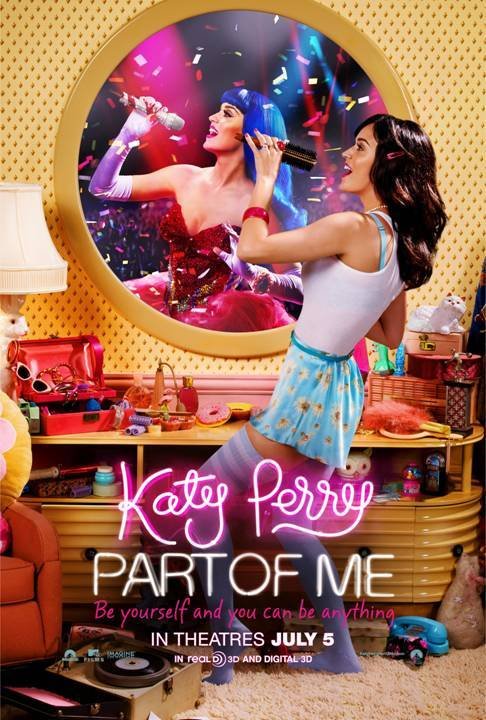

Katy Perry is a bombshell popstar: her candy-colored hair and technologically-enhanced breasts are an almost comic hyperbole of pop iconography. Released in 3D on the Fourth of July weekend of 2012, Katy Perry: Part of Me melded concert footage, behind-the-scenes footage, home movies, and interviews. Using the same narrative formula of the films mentioned above, the documentary frames the story of her rise to pop stardom against the backdrop of her 2011 Part of Me World Tour and her tumultuous personal life (that is, her divorce from comedian Russell Brand). The film fails to deliver a teenage dream or flesh out the reality of being a solitary pop star. However, in its failure, Part of Me also highlights how successful rock docs necessarily traffic in tragedy—not just sadness or misfortune—for entertainment value and to validate their subjects as “true” artists.

Following the massively successful 2011 release of Justin Bieber’s concert movie Never Say Never, Perry’s film (produced by the team behind the Bieber doc) provided what Bieber was not able to provide as a male tween heartthrob: drama of the reality-television sort. Though dazzling concert footage is the visual centerpiece of the film, Perry’s private life provides the emotional core. Russell Brand looms large throughout the film as Perry is shown struggling with the emotional burden of a marriage that’s falling apart.

Perry is seen checking her text messages and looking visibly upset; tense phone calls are followed by members of her entourage looking at her with concern in their eyes. The film slowly builds the tension toward the dissolution of their relationship. The trailer for the movie promises an inside look into Perry’s life, teasing their divorce as a crucial plot point. The film more than delivers this moment, but its intended effect is uncertain.

In the film’s climax, Perry breaks down moments before taking the stage in São Paulo, Brazil, the day the media broke the news of her divorce. She sobs deeply and gasps for breath while her dancers coo, “You got this.” There is a visually-affecting contrast between Perry’s audible pain, the chants of thousands of fans screaming her name, and a crew that is more concerned with the logistics of a possible cancelled show than with Perry’s emotional well-being. Though the filmmakers clearly expect the audience to support Perry when she finally plasters a smile on her face and rises to the stage still choking back tears, those familiar with the rock documentary genre have a palpable sense of this moment as one in a series of moments that could build to eat up even the most resilient stars. As Perry rises to the stage by herself, the film unwittingly captures how Perry’s fame isolates her, even from those supposedly closest to her. Her makeup artists, assistants, and Perry’s own sister confess for months they didn’t know exactly why Perry was upset. The film clearly shows that they, like the media, gossiped and whispered about her. At one point, Perry says through tears, “I can hear you guys talking.” One of her assistants replies, “We know,” and they continue to whisper concerns with Perry a few steps away.

But the stakes in Katy Perry: Part of Me aren’t nearly as high as they are in the Kurt Cobain documentary Montage of Heck or in Amy, a documentary about Amy Winehouse. Both of those films are haunted by the specter of death because the audience is familiar with how their tragic stories end. The filmmakers have a more difficult task in crafting a surprising and refreshing take on the lives of Cobain and Winehouse when their stories are so well-known already. Though both films garnered praise from critics for their ability to make their rather tired subjects new again, both films still rely on a traditional narrative of artistic genius cut short by tragedy. Both films are driven by the knowledge that these troubled musicians are headed to an untimely, and deeply affecting, end.

Montage of Heck is singularly focused on Cobain and his tragedy rather than placing Cobain in a historical context of the evolving punk and grunge scene in 1990s Seattle. The movie’s substance relies on its psychological analysis of Cobain. Though throwaway references to George Bush Sr. and Bill Clinton superficially attempt to connect Cobain to political turmoil outside his inner turmoil, ultimately the film posits Cobain’s musical genius as arising from his own uniquely felt “alienation” from society that was, according to the film, only coincidentally connected to happenings in the outside world. The filmmakers of Montage of Heck suggest Cobain’s pain came from the disjuncture between what was and how he thought things should be. According to the film, this manifested in artwork, poetry, and lyrics that expressed a discontentment with “authority figures,” though there are hints that Cobain was also motivated by a vehement hatred of sexist, classist, and racist hierarchies.

Unlike with Cobain, Amy Winehouse’s music was less about representing a generation of disaffected youth and more about her unique sound and authentic lyrics. In that way, Amy Winehouse was, as the documentary attempts to prove, outside time. Winehouse was a refreshing turn away from the mechanical and fabricated sounds of singers churned out by the British pop music machine at the time and back toward the old jazz greats. In Amy, Winehouse’s inner life is less parsed out—possibly because her confessional lyrics need far less interpretation than Cobain’s series of abstract, visceral phrases. But Winehouse is also characterized as a more reactive figure: she is depicted as a victim of other people who abandon her and dismiss her emotions.

All three films revolve around emotions—love and romance—in similar ways. For Cobain and Winehouse, their all-consuming romantic attachments to self-destructive people are framed as the impetus for their increasing addiction and isolation. By framing them as hopeless romantics, both documentaries reify the common preconception of artists as highly emotionally sensitive people. Their artistic talent is confirmed by their inability to separate love from their work.

Cobain and Courtney Love’s love story was at the center of the Cobain myth even before his untimely death. The documentary attempts to demystify their love by juxtaposing criticism of their relationship from friends, family, and fans with home videos that range from charming to disturbing. Courtney Love’s own acknowledgement of their family unit as both incredibly traditional and totally “fucked up” encapsulates their relationship. Their torrid love affair is both alluring and utterly irrational.

Amy proposes that for Winehouse, her staunch creative independence was countered by her over-reliance on the approval from the men in her life, namely her father and her husband. The film shows how Winehouse was most creatively productive during times of heartbreak, taking material straight from her life and translating that into her most powerful song lyrics. Though Amy presents us with the point of view of Blake Fielder-Civil, Winehouse’s husband, it is also careful to position him as an unreliable narrator. Unlike Montage of Heck, Amy is far more critical of her romantic relationship. This may be in large part due to Winehouse’s own character rendering. She is depicted both as an artist and as a performer, a term synonymous with pop stardom, which relies less on artistic talent than on charisma. Winehouse was a romantic and sensitive performer, who, at first, prioritized her career above all else. However, as the film describes it, she became more isolated as demands on her artistic production increased. Her isolation made her more prone to Fielder-Civil’s influence.

Both documentaries, careful of romanticizing drug addiction, argue that it wasn’t just love and approval that these musicians were seeking. They do this by reciting that addiction is a disease and by recounting various pleas of family members for rehab and intervention. However, both Winehouse and Cobain are described as doomed long before they have their first taste of drugs. As children they were “special” or “different” or “wise beyond their years.” From the outset they were doomed because they were artists.

It is Perry’s refusal to be consumed by love that ruins her marriage. Perry herself frames the divorce as a choice between marriage and her career, opting out of motherhood and “slowing down” in favor of riding the fame wave. In contrast to the other two films, this move seems like the decision of a savvy businesswoman, not that of a romantic “artist.” Part of Me attempts to excise sadness by saturating the rest of the film in pyrotechnics, dancing, and general whimsy. Only a few moments after her backstage breakdown, images of supportive fan Tweets fill the screen, deftly undercutting the wrenching moment. For Perry, it is her fans (and, possibly, fame itself) that buoy her in times of need.

However, despite Perry’s and the film’s attempts to craft a triumphant and empowering narrative, Part of Me never fully recovers. The film’s closing concert sequence is haunted by the knowledge that Perry sometimes forcibly performs happiness—did she just cry before that final performance too? Will she be okay? How can she be okay? Part of Me ends where the tragic story begins in the other documentaries. As if Amy had ended on a high, when heartbroken Winehouse made Back to Black—Winehouse’s most commercially successful album. But despite the lingering questions left at the end of Part of Me, the film itself does everything it can to ameliorate concerns about Perry and her well-being.

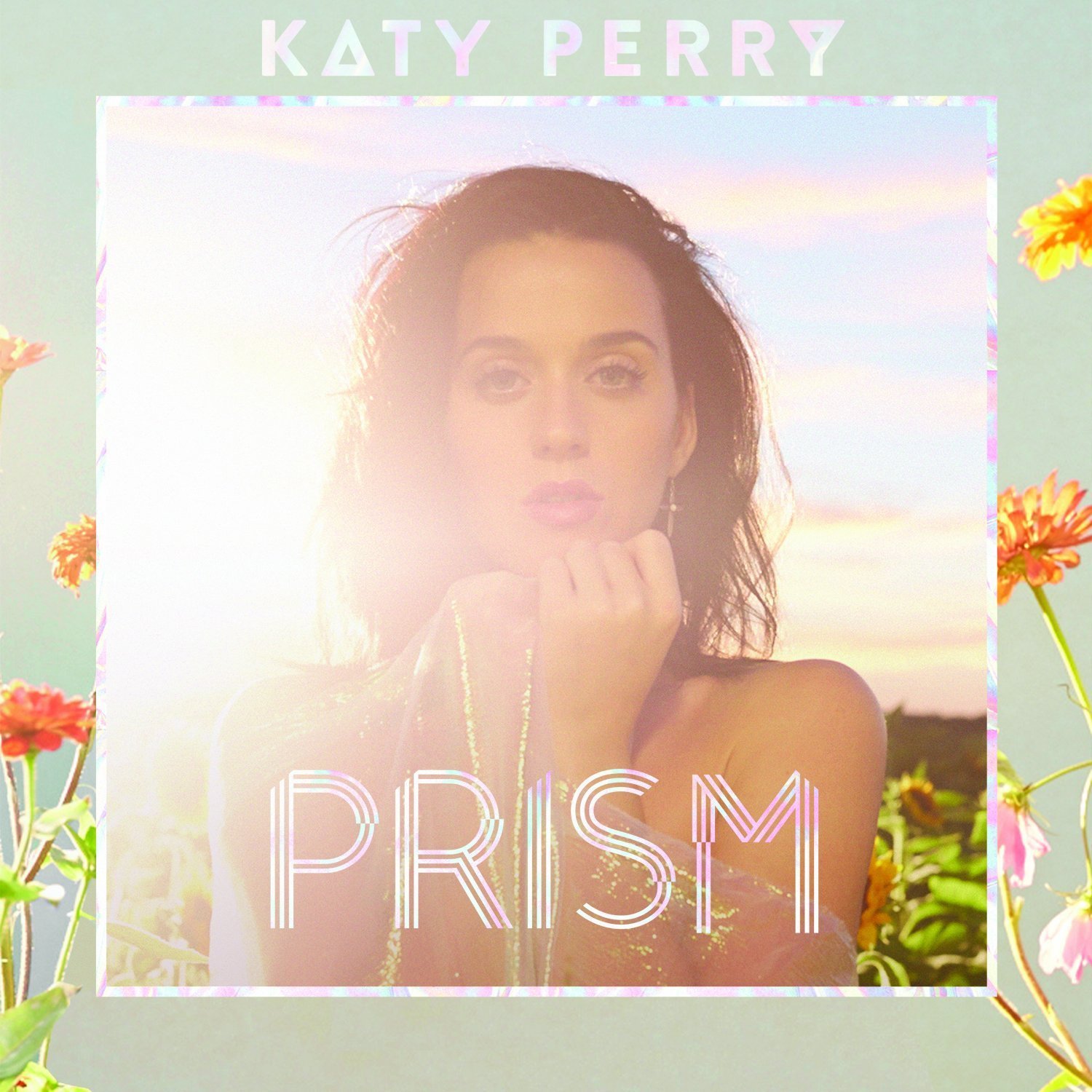

Post-divorce Perry attempted to capitalize on the connection between pain and artistry by penning the lyrics for her most personal album, where she “confronts her turbulent recent history,” according to Billboard Magazine. The album, Prism, was supposed to capture pain in a way that a team of pop songwriters wouldn’t be able to do. It was not only her comeback from divorce, it was going to usher in a stripped-down version of her bombastic persona (as seen on the cover of the album). But Perry is still not associated with creative genius in the way Winehouse and Cobain are. Many will argue this is because there are actual differences in talent, and this may be so. But what documentaries like Montage of Heck and Amy successfully do is make tragedy seem inevitable from the outset. The childhoods, teenage years, and adult lives of their subjects are burdened by their tragic futures. Many of the qualitative “differences” between Perry and a slew of tragic music legends rely on an image of a tragic romantic artist deeply intertwined with our definitions of “quality” and “authenticity.” Tragedy works as a tool with which the filmmakers validate the artistry and talent of the subjects, and to conflate “tragedy” with artistic genius is a dangerous move. Katy Perry: Part of Me may be a better movie because it doesn’t make this easy connection, but it also fails because, without this connection, the movie can so easily be dismissed as unsubstantial and tragically boring.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.