Bullets, Syphilis Cosmetics, and Archaeologist Cat Fights: Notes From My Saturday Afternoon

Photo by the author for Dilettante Army

On a recent Saturday, I came face to face with the world historical forces of trade, technology, colonialism, and bureaucracy, by which I mean I ran some errands. In February, I wrote in Dilettante Army about how my fascination with the provenance of objects led me to research the origin and meaning of a mysterious, penis-shaped piece of metal [1]. This time I turn my attention to a set of more ordinary items, those things I acquired over a Saturday’s-worth of errands.

On the Saturday in question, my to-do list looked like this:

-get keys made

-haircut

-beeswax for pysanky

1st Errand: Keys

First I walked to a hardware store in my neighborhood to make three copies of my house keys. It took roughly two minutes for the hardware store employee to run the blanks through the automatic key cutting machine and cost $4.50 in total. The space of those minutes contains millennia of human innovation and argument, of keeping out and keeping in. My house key fits a standard pin tumbler lock — two concentric cylinders with spring-loaded metal pins that are forced up only by the right key, allowing the cylinders to turn and the lock to open. Also called a Yale lock, it was invented in 1848 by Linus Yale, Sr. His son Linus Yale, Jr. improved the design and patented it in 1861 [2]. The elder Yale was reportedly inspired by wooden pin locks thought to be created by the Egyptians in roughly 4,000 B.C.E. But here is where things get murky.

Lock historians seem to wind their panties into Gordian knots trying to pinpoint the origin and precise nature of ancient lock and key systems. While the idea of 6,000 year old Egyptian lock is frequently tossed around in scholarly work and popular history (and was no doubt an inspiration to Yale), the existence of such an object at that time is not necessarily supported by the archaeological record. The wooden pin locking mechanism that has been called the Egyptian lock did not actually appear in Egypt until the Roman period [3].

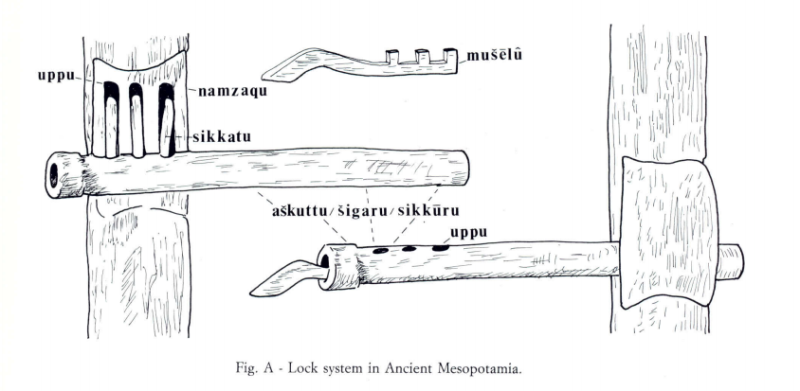

Image via Dan T. Potts in “Lock and Key in Ancient Mesopotamia”

The mechanism may have originated in ancient Mesopotamia, but such claims are a source of fierce disagreement among scholars. “Although archaeological evidence for early locks remains slight, the lexical field has been well-surveyed,” writes archaeologist Dan T. Potts [4]. With little in the way of surviving physical locks and keys, the raging controversy lies in the translation of their descriptions on cuneiform tablets. While some historians assert that the locking mechanisms described are of simple cross bars, Potts believes that Sumerian and Akkadian scribes in fact wrote about pin tumbler locks as early as 2,000 B.C.E.

Regardless of their precise origin(s), locks and keys are enduring practical objects steeped in evolving symbolic meaning. They are associated with knowledge, heaven, the Pope, marital fidelity, etc. depending on who, and where, and when you are. Author Helen Oyeyemi’s new collection of short stories What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours explores her longtime fascination with keys. “I think keys can cut — it divides property, it separates what is yours from what is not yours. A key defends what you have, but it also protects other people’s property from you,” she said in an interview with NPR [5]. The urge to delineate property, to seal out and seal in is a very old human impulse. When I was in high school, I once returned to a deserted parking lot late at night to find that someone had smashed the window of my car and stolen a backpack — full of textbooks and a graphing calculator — from the back seat. The icy sense of unease that crawled up my spine was not simply a reaction to the loss of property. As anyone who’s had their home or car or workplace broken into can attest, there is an unshakeable feeling of violation that comes with the burglar’s decision to circumvent the lock and key. A key is a contract.

2nd Errand: Hair Powder

I left Mesopotamia and set off on my next errand. I like to get frequent trims at a barbershop in Williamsburg staffed mainly by queer lady scissor-whizzes. My barber performed her usual witchcraft. Afterwards, as I paid for my haircut, I also bought a bottle of texturizing hair powder. Ingredients: aqua, silica silyate, vp/va copolymer, alcohol, sodium benzoate, citric acid. Ten grams of the fine, white, odorless powder set me back $25.

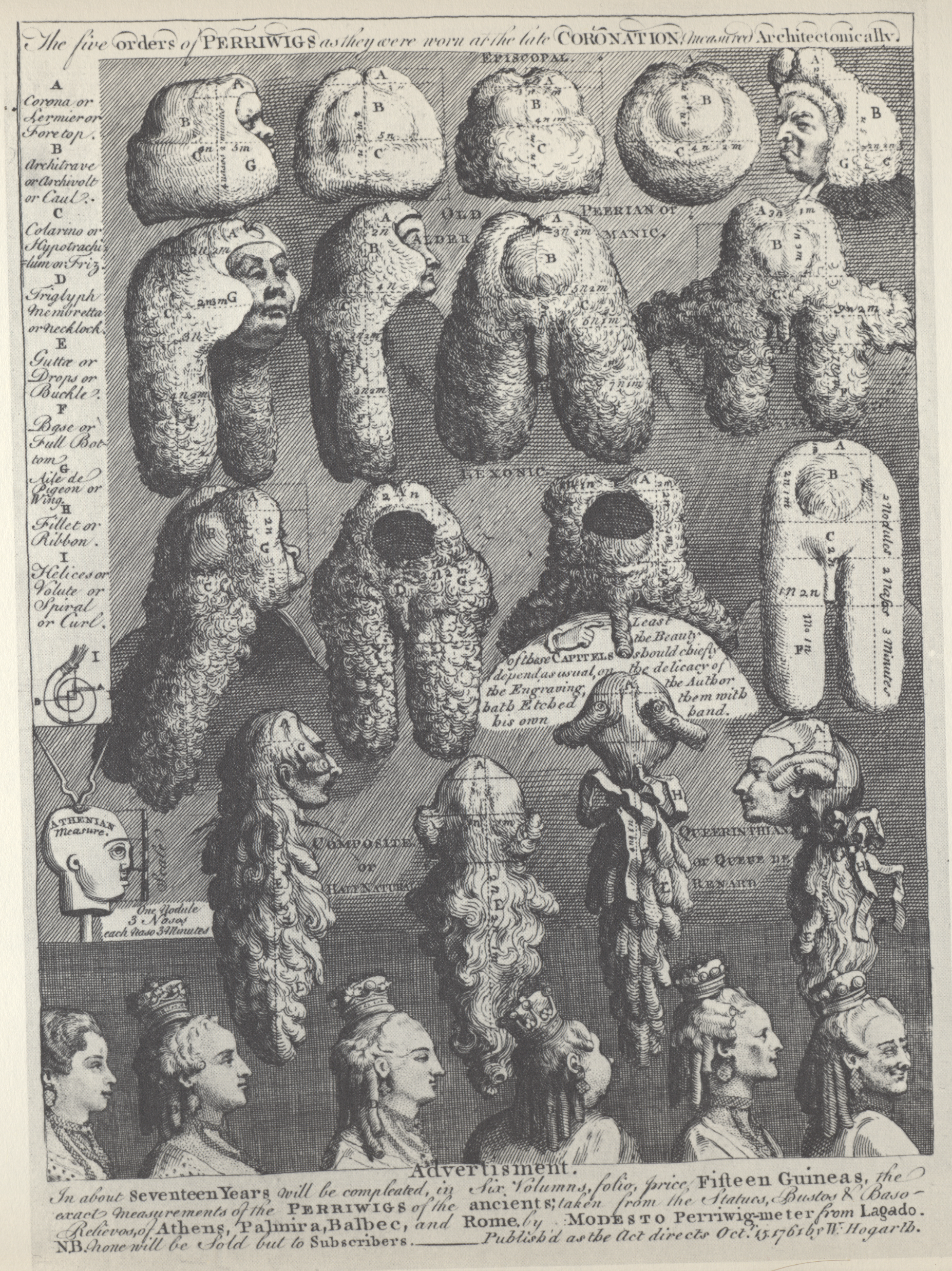

The hair powder I bought may be a modern concoction, but it harkens back, at least in name, to a much older commodity with a fraught cultural history. Hair powder or wig powder — called both because it was used both on wigs and natural hair — was popular across France and the British Isles in the 17th and 18th centuries, when wigs were “kind of a big deal” [6] as high-status fashion items. The powder, usually low-grade flour scented with lavender or orris root, gave wigs their distinctive off-white color.

The rise of wigs, face powder, and beauty spots in King Louis XIV’s court can be tied to the spread of syphilis. These were cosmetic solutions for physical deformities and stinking sores [7]. Here you will thank me for not including images of syphilitic leg ulcers.

The Five Orders of Perriwigs as they were Worn at the Late Coronation Measured Architectonically, William Hogarth, 1761

In Great Britain, the downfall of hair and wig powder began with the Duty on Hair Powder Act of 1795. According to historian Kenneth R. Johnston:

It was an issue of such patent ridiculousness, arcane technical detail, and deadly serious political consequences that it challenges one to find something similar in contemporary life. Imagine if the Bush White House proposed a special tax on the use of hair sprays and gels to finance his Iraq adventure. Most intelligent writers on the issue in the 1790s, pro or con, had a hard time keeping a straight face when discussing it.[8]

The Hair Powder Act did not tax the commodity itself (which was, after all, ordinary flour), but the use of it. As a luxury tax, it was designed to make the upper classes shoulder the financial burden of increasingly unpopular and expensive wars in Australia and the Caribbean [9]. In order to levy and collect the tax, a large, often intrusive bureaucracy emerged, and, Johnston argues, catalyzed a crucial breakdown of notions of the private sphere.

Though hardly as obvious as a powdered periwig, my hair powder too is a luxury commodity that functions as part of my social performance. Thankfully, it does not smell like syphilis and colonial aggression.

Interlude: Ice Cream and Beer

Photo by the author for Dilettante Army

Freshly shorn and feeling peckish, I stopped for an ice cream cone and then dropped in on a friend’s birthday party and had a beer. There is not space here to trace the whole route, but through these two pleasurable acts of consumption, I spent $9 and traversed the brutality of the sugar trade, the push and pull of the American temperance movement, the evolution of cooling technology, and so on and so forth into the indefinite minutia of history and historiography.

3rd Errand: Beeswax

Photo by the author for Dilettante Army

Finally, I headed into Manhattan to buy beeswax tablets at the Ukrainian Museum gift shop. I planned to have some friends over the next day to decorate eggs in the Ukrainian style, and I was running low on supplies. Pysanky, or Ukrainian Easter eggs, are dyed using the wax-resist method, through which hot beeswax seals in layers of bright dye. Four beeswax tablets cost $7.

The list of uses of beeswax throughout history is far longer than my attention span. Candles, tooth fillings, cosmetics, didgeridoo mouthpieces, bullet sealants — these are just a few. Even my lowly craft supplies seem to plant themselves at the intersection of ingenuity and destruction, of light and art and the essential human impulse to preserve the body. Objects are never as simple as their forms and basic functions, of course. They carry with them thorny histories, long commodity chains, and hidden moral weight. For $45.50 and all the open source scholarly articles I could find on the internet, I linked and re-linked myself once again to my bloody, brilliant, batshit human history.

[1]Bennett, Molly Jean. “Dick Pics For Sacred Healing: A Meditation on the Provenance of Objects.” Dilettante Army. 2016. Accessed 2016. https://dilettantearmy.com/lies/dickpics

[2]Graham-Cumming, John. The Geek Atlas: 128 Places Where Science and Technology Come Alive. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media, 2009. pp. 445

[3]Potts, Dan T. “Lock and Key in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Mesopotamia 25, 1990. pp.185-192

[4]ibid.

[5]Inskeep, Steve. “Keys Are The Key To ‘What Is Not Yours.’” NPR. 2016. Accessed 2016. http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=470878476

[6]Van Houten, Evangeline. “Wigs and Tories: The Shallow Brilliance of Colley Cibber.” Dilettante Army. 2016. Accessed 2016. https://dilettantearmy.com/facts/colley-cibber

[7]Hach, Wolfgang, J. Dissemond, and V. Hach-Wunderle. “The long road to syphilitic leg ulcers.” Phlebologie 2, 2013. pp. 1-7

[8]Johnston, Kenneth R. “Review of The Spirit of Despotism: Invasions of Privacy in the 1790s by John Barrell; Trials for Treason and Sedition, 1792-1794. Volume I, Introduction + Trials of Thomas Paine (1793), John Frost (1794) and Daniel Isaac Eaton (1794). Volume II, Trial of Thomas Hardy (1794), vol. I Volume III, Trial of Thomas Hardy (1795), vol. II Volume IV, Trial of Thomas Hardy (1795), vol. III Volume V, Trial of Thomas Hardy (1795), vol. IV by John Barrell, Jon Mee.” The Wordsworth Circle 37, 2006. pp. 196-199

[9]ibid.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.