Ambiguous Maps and Border Shadows: Towards a Gradient Divide

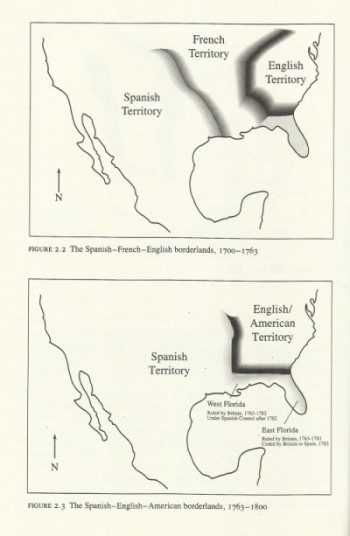

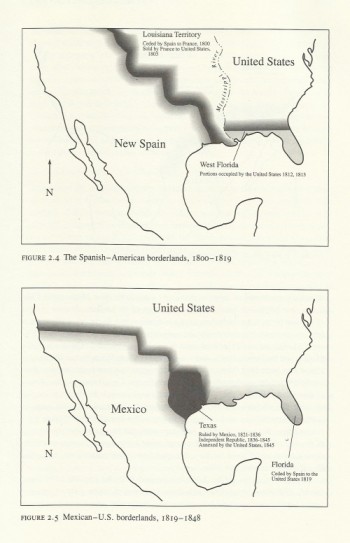

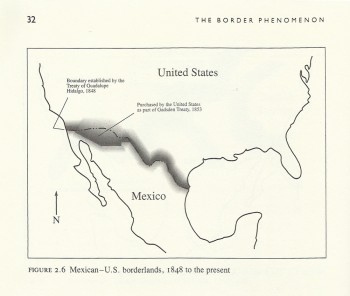

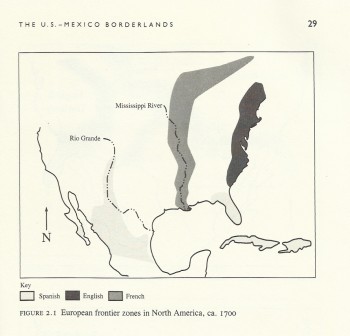

While reading a book about life and society on the US-Mexico border I became fascinated by this set of maps. Excluding the first picture, which simply gives us Spain, England, and France isolated in a relatively blank visual field, the images express a  dynamism that unfolds across time. They articulate how volatile and in motion the US-Mexico border was from the early 1700s through the mid 1800s. But more importantly the maps employ gradation to illustrate, and not overdetermine, the assorted influence that each major European power had on the variously shaped and misshaped American territories. The nuanced intensity of the gradient border lets us know that these contentious boundaries were more than a series of sterile strokes—they were zones of interaction with many steps and degrees, as much about cultural leakage as containment. Black ink fades into gray indicating some other kind fading into. The maps do not simply impart spatial, geographic, or nationalistic facts. They do not divide the world into coherent and easily knowable segments with easily defined cultural categories—logico-epistemological cultural space. Some other type of information is given in the softness of the boundaries.

dynamism that unfolds across time. They articulate how volatile and in motion the US-Mexico border was from the early 1700s through the mid 1800s. But more importantly the maps employ gradation to illustrate, and not overdetermine, the assorted influence that each major European power had on the variously shaped and misshaped American territories. The nuanced intensity of the gradient border lets us know that these contentious boundaries were more than a series of sterile strokes—they were zones of interaction with many steps and degrees, as much about cultural leakage as containment. Black ink fades into gray indicating some other kind fading into. The maps do not simply impart spatial, geographic, or nationalistic facts. They do not divide the world into coherent and easily knowable segments with easily defined cultural categories—logico-epistemological cultural space. Some other type of information is given in the softness of the boundaries.

The blur, the shadow, the haze, these are untidy approaches to understanding what is commonly thought of in terms of a hard line, a fence line, or an autonomous, abstract, and virtual distinction—“the border.” There is the US on one side and Mexico on the other, until it changes again. The blur is untidy, but it is also generative. All maps are ideological, generally echoing back clarity and differentiation; these maps, however, are suggestive metaphors that lead our thinking toward the acceptance and acknowledgment of cultural diffusion, interaction, messiness, interdependence, contamination, and hybridity. They illustrate the difference between a border and the borderlands: the prior being an intangible abstraction and the latter being all too real. And although the map’s gradations end, in lived-life they continue, flowing into the US, spreading across and filling its façade. The gradient border is not simply a concept that exists separate from the world. These are maps of physical places where people lived and continue to live, people who faced and still face material borderland consequences, who travel beyond the borderlands (and also return).

“A border is a line that separates one nation from another or, in the case of internal entities, one province or locality from another. The essential functions of a border are to keep people in their own space and to prevent, control, or regulate interactions among them. A borderland is a region that lies adjacent to a border. The territorial limit of a borderland depends on the geographic reach of the interaction with the ‘other side.’ Some borderlands are physically small because foreign influences are confined to the immediate border area; others are large because such influences penetrate far beyond the border zone … A related term, frontier, denotes an area that is physically distant from the core of the nation; it is a zone of transition, a place where people and institutions are shaped by natural and human forces that are not felt in the heartland.”*

“A border is a line that separates one nation from another or, in the case of internal entities, one province or locality from another. The essential functions of a border are to keep people in their own space and to prevent, control, or regulate interactions among them. A borderland is a region that lies adjacent to a border. The territorial limit of a borderland depends on the geographic reach of the interaction with the ‘other side.’ Some borderlands are physically small because foreign influences are confined to the immediate border area; others are large because such influences penetrate far beyond the border zone … A related term, frontier, denotes an area that is physically distant from the core of the nation; it is a zone of transition, a place where people and institutions are shaped by natural and human forces that are not felt in the heartland.”*

I have been wondering about the heartland, especially while thinking of maps, boundaries, blurs, hazes, gradients, and the US-Mexico border, while thinking about centers and outskirts. Given these maps it appears as if most of the US is or was a borderland at some point. Nevertheless, there is also a heartland somehow, constructed in opposition to the gradient. And if there  is a hermetic heartland can there be a land of hands, arms, feet. Is the heart really the sacred and central locale that defines the true nature of a person, place, or thing? I’d rather live in the armland of the US, a land that is periphery but crucial, that holds on tight, that has the ability to cause action, to write, to brace, to lift up, to carry things over, to reach deep into the “other side,” into the heart, into the land, to transform and remold what it comes into contact with. The armland is always in motion, an appendage emanating from a center, but never a center itself. No not that, not the arm connected to the center. It is a crooked centerless shadow radiating from moments of contact, made of many ascents and descents of tone and complexion; it is a mass of bodiless arms bending to bring the physically distant “other” close, searching far beyond the routine border zone into the places and institutions that define the US and Mexico as oppositional and different, yet commingled and codependent.

is a hermetic heartland can there be a land of hands, arms, feet. Is the heart really the sacred and central locale that defines the true nature of a person, place, or thing? I’d rather live in the armland of the US, a land that is periphery but crucial, that holds on tight, that has the ability to cause action, to write, to brace, to lift up, to carry things over, to reach deep into the “other side,” into the heart, into the land, to transform and remold what it comes into contact with. The armland is always in motion, an appendage emanating from a center, but never a center itself. No not that, not the arm connected to the center. It is a crooked centerless shadow radiating from moments of contact, made of many ascents and descents of tone and complexion; it is a mass of bodiless arms bending to bring the physically distant “other” close, searching far beyond the routine border zone into the places and institutions that define the US and Mexico as oppositional and different, yet commingled and codependent.

*Oscar J. Martinez, Border People: Life and Society in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 1994), 5. All maps from same volume.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.