The Loud Silence of Monuments

Monuments are not only material constructions; they are also conceptual constructions. Their physical scale is usually meant to make physically manifest the great weight and scale the events they reference hold in a collective consciousness. Monuments are erected as historical talking points—far from simply evoking memory, they provide instruction. They are demands made by a past body of people that we honor their values in the present.

More than a marker, the monument is also a speech act. As such, its logics of representation and interpretation can be explained with recourse to the field of semiotics—a branch of linguistics founded in the early twentieth century by the English theorist Charles Sanders Pierce. Differentiating the terms icon, index, and symbol, Pierce provided an enduring theory of representation and of language that can inform how even a non-linguistic act or object, such as the erection of a monument, recruits agreed-upon terms in order to (ideally) effect an interpretive consensus.

To briefly review: the index points to the meaning, and the icon resembles the meaning. The symbol is the messiest of these and the one that bears the most ideological weight. It is constructed culturally and relies upon consensus in order to be effective. A symbol has to be recognizable in order to function. An unrecognized symbol is not a symbol; it is at best a mark indicating not much more than the intention of an agent.

The monument is assumed to have a symbolic (if not indexical) relation to an event determined to be momentous. The various semiotic chains that link the monument to the event speak directly to the project of signifying. Through these manipulations, an agent manipulates a term in order to convey meaning to someone else.

Confederate monuments, for example, are rightly understood as symbols. Some of them are also iconic, in that they represent a particular figure, or indexical, in that they point to an historical moment. Often, that historical moment is an alibi for an idea about what that moment meant (i.e., “the monument is about the Civil War which was about Southern pride which has nothing to do with white supremacy and slavery”).

But even if the monument survives that bad-faith indexical chain, it falters upon the field of symbolism, where consensus is what matters. And essential to this appreciation of consensus is knowing that it is not always volitional; it is conscripted. In fact, being a member of a cultural group—let’s say the US—is contingent upon understanding the symbolic terms. One doesn’t get to opt out of the significations of the majority. The dominant message does just that: it dominates. It does not necessarily convince.

Monuments strive toward permanence. They are intended to surpass the duration of the event that they reference. With hard and heavy concrete, granite, bronze, and steel, monuments signal their immovability and permanence. Their erection in these decay-resistant materials makes them, much like gravestones, stalwarts against the fleshly world’s “failings” of memory, mortality, and disintegration.

Like photographs, monuments make plain their attempt to undo the insufficiency of memory. If photographs not only preserve the eventual loss of the object before the lens, they also predict it. This wisdom about photographic technology, so beautifully and pathetically rendered by the French philosopher Roland Barthes in his volume Camera Lucida, lends itself well to unpacking the logic of the monument. One can imagine the great stone moved into a location teeming with quickly evaporating memories of the moment, the just-passed event like a kind of colossal paperweight, holding down time and meaning.

Some of us are pinioned by the monument that is meant to buoy others. Monuments do, after all, occupy lives and land. Unlike literary inscription, they must be public (though they define the public in their own way) and instantly recognizable as great statements. In literary-based societies, before the advent of vellum and parchment, literary inscription and the monument were one and the same. Only those thoughts deemed worthy of permanent remembrance were consigned to the carver’s care. The Rosetta Stone is one example; the hieroglyphs of ancient Egyptian and Mayan societies are but two others. The objects in both of these examples resonate with the sacred and essential elements of their respective societies, pointing to the idea of the monument as a universal touchstone, providing order to a people in the present through a spiritual and often cosmological understanding of their connections to the past and the future. A monument is the tie that binds. It is a sacred pact that human beings make with their world.

It is no accident, then, that monuments invoke death even as they seek to stave it off. Whereas the death of the body is inevitable, the monument, it is wished, will preserve the memory. The gravestone and mausoleum serve this purpose. They are markers to be visited by loved ones and others impacted by the loss, so as to say that a life had been lived and mattered. But when the scale and circumstances of death exceed the personal to encompass also the communal, the gravestone is considered not enough, and must be inflated to proportions understood to be more appropriate to the grandeur of the loss experienced.

Part of the problem with the Confederate monuments is that they do not only mark deaths, but they also mark their cause. More than the deaths of masses of young men, confederate monuments in particular mark the death of the Confederate cause, a significant portion of which was the Confederate states’ commitment to the preservation of slavery. To that end, these monuments refuse to let die the social touchstone of white supremacy and black subjugation.

Similarly, monuments to colonization—be it the arrival of Christopher Columbus or Spanish missionaries—refuse to let die a social commitment to manifest destiny and native genocide. Decolonization is, also, necessarily conceptual. Its work is not only redress against a white supremacy that degrades and instrumentalizes Black bodies and interests, but also redress against a white colonialism that continues to degrade and erase red bodies and interests.

Confederate monuments are embedded in a struggle over the identity of the South in the US national context. This may seem a supposedly simple regional configuration, but it is, in fact, a geographical imaginary inflected by temporality and relationality—the time of settlement, the relationships between the North and South as well as those between Black and white, settler and native, enslaved and free, citizen and insurgent. In other words, the South is not just the Other of the North. It is contiguous with a history of settler colonialism that affects the entire hemisphere known as the Americas. The Civil War and the South’s Confederate legacy overdetermine a thicker and richer appreciation of what the battle over monuments is about—the decolonization of space.

Indeed, the idea that that the monuments to the Confederacy were, by and large, erected to honor the deaths of Confederate soldiers and acknowledge the particular heritage of the US South has been exposed as an ideological fiction. A 2019 report from the Southern Poverty Law Center dispels the fiction that the monuments were established directly in the wake of the Civil War and for the apolitical purpose of celebrating a universalist ideal of Southern heritage. The erection of monuments and other dedications (such as naming) in fact occurred well beyond the boundaries of the South, including two public elementary schools in southern California that were named after Confederate General Robert E. Lee and as far north as Washington State, where Lee Elementary School has been welcoming students since 1955.

Perhaps more damning evidence that the Confederate monuments are less about memory and more about instruction is the fact that the vast majority of the commemorations appeared between the years 1900 and 1920, with an additional upsurge during the Great Depression (1929 – 1939) and the Civil Rights Movement (1954 – 1968). As Columbia University historian Eric Foner explained in a 2017 op-ed for the New York Times, “The great waves of Confederate monument building took place in the 1890s, as the Confederacy was coming to be idealized as the so-called Lost Cause and the Jim Crow system was being fastened upon the South, and in the 1920s, the height of black disenfranchisement, segregation and lynching. The statues,” he concludes, “were part of the legitimation of this racist regime and of an exclusionary definition of America.”[1]

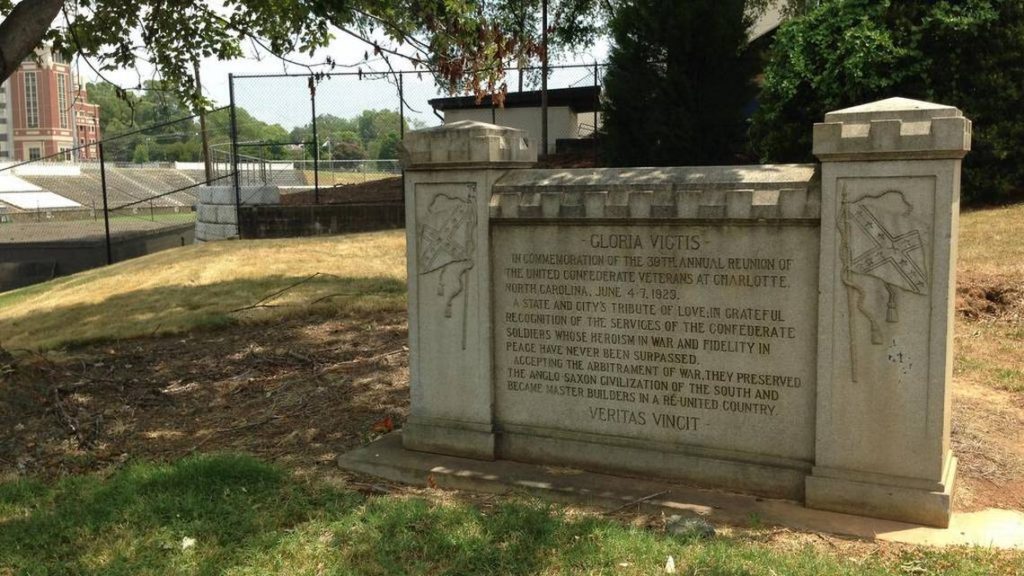

1929 Confederate Reunion Marker, Charlotte, NC. Photo via Erin Bacon and the Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, UNC Chapel Hill Library

Foner’s interpretation of the monuments’ purpose is ratified by the declarations of the monuments themselves. The 1929 Charlotte, North Carolina monument to Confederate veterans dedicated by “citizens of the city of Charlotte and the county of Mecklenburg” boldly states its purpose as “A state and city’s tribute of love, in grateful recognition of the confederate soldiers whose heroism in war and fidelity in peace have never been surpassed. Accepting the arbitrament of war, they preserved the Anglo-Saxon civilization of the south and became master builders in a re-unified country.”[2] Far from bemoaning the passage of the soldiers’ mortal remains, the monument emphasizes the perpetration of their cause, which it describes unequivocally as white supremacy.

Just as monuments were erected to bring the Lost Cause of white supremacy insistently into the present, so too were they created to erase Native American presence and script a national history as one commencing and carrying through with the principles of colonization and conquest. In New York City in particular, more than one hundred artist- and scholar-activists have brought a vibrant challenge to the commemoration of such figures as colonizer Christopher Columbus, eugenicist gynecologist J. Marion Sims, and French Nazi collaborators Phillippe Pétain and Pierre Laval. In 2017, the activists authored a letter signaling the radical incommensurability of these monuments with “a city whose elected officials preach tolerance and equity.”[3] Importantly, they do not, as some detractors have claimed, call for a wholesale erasure of history—an evacuation of the spaces and silences in the faces of history’s claims to a roundly unjust past. To the contrary, they consider the removal and relocating of monuments as speech acts in themselves, offering redress to violent, bigoted legacies and greeting the clamor from some quarters of the past with calls of their own. “We understand this call for removal as an historic moral opportunity for creatively reckoning with the past and opening space for a more just future. We encourage the Commission to seize this opportunity to make a brave, even monumental, gesture that will resonate for generations to come, rather than a politically expedient fix that will be easily absorbed–and quickly forgotten–by the status quo.”[4] The New York group’s recruitment of their voices to challenge the symbolism of racism and settler colonialism calls out the false claims to indexicality of these monuments, forcing them to meet on the same discursive, representational terms, to battle once more for the soul of the people.

Implicitly at stake in this confrontation is the identity of the community that is hailed by the moniker “public.” It is therefore certainly worth noting that several of these public monuments occupy institutions of education, both public and private. We should attend to the presence of monuments in these locations and to the connection that they therefore draw between knowledge and exclusionary power. At the university campus and other educational spaces, the community’s membership and commitments are arguably even more neatly defined than they are in the vast expanses of “public spaces” (where “public spaces” almost always refers to lands seized by war and deceit in the name of advancing the interests of a more proper, i.e. non-Native, public). These institutions are themselves inscribed in racialized histories of exploitation and occupation and therefore function as monuments, albeit more insidious ones perhaps, to the interweaving of wealth, power, and knowledge in U.S. society and more generally in the modern West.

Postcard of the unveiling of Silent Sam, June 2, 1913. “Unveiling, 1913,” UNC Libraries

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a bronze statue commemorating the Confederacy presided over one of the university’s central courtyards. “Silent Sam,” as the statue was called, stood until August of 2018 when it was toppled by protestors. The remaining plinth was removed by decree of the school’s chancellor, Carol L. Folt, in response to impassioned calls from multiple quarters of the state and the university. Folt did not survive in her leadership position for very long after directing the removal of the statue’s base. After tendering her resignation in January 2019, to be enacted at the end of June 2019, Folt’s timeline for departure was abruptly shortened to just a few weeks. Rather than an innocuous vestige of a historically discreet attitude (the statue was erected in 1913 at the behest of the United Daughters of the Confederacy after a campaign that began in 1908),[5] Sam’s “silence” spoke loudly about what its commissioners saw as the proper order of the institution, one in which, as then-trustee Julian Carr explained at the dedication in 1913, “the Confederate soldier [oversaw] the welfare of the Anglo-Saxon race,” emboldening him “[o]ne hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from [the battle at] Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted an maligned a Southern lady, and then [I] rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterward slept with a double-barrel shotgun under my head.”[6]

Perhaps silent, but surely a sentinel and more: Sam was erected to stand as a bulwark against an insurrectionary African American populace—not yet considered a public—aiming to guarantee that the order of white men reigned in this land. Silent Sam’s “silence,” as African-American literary scholar Kevin Quashie might put it, is better understood in fact as a speech act that testified to white dominance in the subsonic key of Black and Native American obliteration and absence.

Protest at Silent Sam site, August 22, 2017. Photo by Rodney Dunning (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Looking at the university also reveals the inadequacy of the North-South dyad in unpacking the logic of confederate monuments. As institutions historically dedicated to the education of a ruling class, universities throughout the country, but in particular those founded before the Civil War, contend with their racist and exploitative inheritances. This reckoning has prompted numerous private institutions of higher education—many of which have educated and employed men who furthered missions of eugenics, slavery, Jim Crow, and settler colonialism—to invent their own reparations. Those reparations have taken the form of scholarships to the descendants of those the university held in slavery (Georgetown) and forms of marking, through renamings (Yale) and the dedication of memorial plaques (Harvard), the people who were forcibly displaced and exploited in the name of academic progress. In 2016, following three years of organizing, Columbia University laid a plaque in honor of the Lenape people, the original inhabitants of the land on which Columbia was erected in 1877. Efforts such as these can offer an engagement with the past and a useful rededication to the project of knowledge creation and dissemination, this time with a more inclusive notion of the public and a greater sense of justice. Commenting upon Columbia’s formal acknowledgement of the Lenape, historian Karl Jacoby remarked that “once we know this past, we need to ask what the responsibilities of this knowledge of our history place on us, the living.”[7] It is not simply an issue of pulling down some monuments to make room for others. Rather, at issue is a more complete knowledge of the present as a consequence of the past that can be ethically addressed as we move, collectively, into the future.

Monuments are not, therefore, “out” or passé. They are rich sites for creative reworking of communal memories, the best of which point back to the interrogate the desires and goals of those who would seek to supplement their memories and histories with prosthetic objects. Quite often, the scale of a monument tells us something about the cultural value of the momentous event or figure. Fortunately, that technique or condition—rendering a meaning out of scale, sometimes literally inflating its proportions and significance—is, at least in theory, available to anyone. It is in this slice of freedom—what philosopher Jacques Derrida, improving upon the work of Charles Sanders Peirce, termed semiotic “play”—that meanings may be altered and the security of meanings may be confronted. Put simply, scale is a register in which outdated, bigoted monuments might fall.

Ti-Rock Moore, New Wars. New Stories. New Heroes., 2017.

Archival inkjet print of time-based performance featuring Nicolas Brierre Aziz at Beauregard Plinth – New Orleans. Courtesy of JONATHAN FERRARA GALLERY New Orleans.

A number of current working artists are engaging with idea of monuments and monumentality. New Orleans-based artists Ti-Rock Moore, who is white, and Nicholas Brierre Aziz, who is Black, took advantage of the midnight removal of monuments in their home city to produce a number of images and videos born from the action of installing the black Aziz atop the plinths designed to uphold white Confederate generals such as P. G. T. Beauregard. They describe the work, entitled New Wars. New Stories. New Heroes., as “a time-based piece that utilizes the power of space and insignia to ignite new dialogue and deconstruct a representation that continues to impede the intended ideals of this nation.”[8]

Another white artist, painter Chris Barnard, turns to painting to highlight the interaction of art historical narratives of white supremacy in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional space. In the 2019 painting Dainty. Innocent. Pure. Barnard recruits linear perspective—an “invention” figured by a Western art-historical narrative as the high mark of artistic achievement—to present a stand-off between two recognizable sculptures that have themselves been objects of a patriarchal white settler gaze. Beneath a light-emitting grid, Edouard Degas’s ubiquitous Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer, occupies the foreground and center of the frame. To the left, in the background but also almost centered, is a likeness of Cyrus Dallin’s 1909 sculpture Appeal to the Great Spirit that stands before the entrance to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Through the juxtaposition of subjects (a Native American on horseback and a young white female dancer), the onlooker is invited to think about the stories of gender and settler colonialism that have been cast as monuments figuring Native peoples and girls as objects of inspection, all while a patriarchal Western institution stages the encounter and recedes into the background.

Chris Barnard, Dainty. Innocent. Pure., 2018-19, 80 x 66 in., oil on canvas over panel. Credit: © Chris Barnard. Image courtesy the artist and Fred Giampietro Gallery.

Perspective and monumentality are also at the center of Japanese artist Tatzu Nishi’s 2012 Discovering Columbus—a site-specific project that entailed the building of a contemporary living room space at the top of the seventy-six-foot column in Columbus Circle in New York. The installation invited visitors to encounter Gaetano Russo’s 1892 Columbus monument in an intimate and far less reverential environment, calling into question the need to place a putatively universally-revered figure at such a remove from the public.

Sanford Biggers, Laocoön, 2015. Vinyl, electric air pump, 10 x 6 x 6ft. Image courtesy of Sanford Biggers Studio.

The power of scale and the question of which figures merit a monument returns in the recent work of two celebrated African American artists. Kara Walker’s 2014 A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby—a “sugar sphinx” made of refined white sugar resembling a hybrid mammy and sphinx and housed in the since-demolished former Dominos sugar factory, and Sanford Biggers’s 2015 Laocoön, an oversized inflated vinyl balloon depicting a cartoonish black boy supine on the floor, render the abjected figures of black masculinity and femininity into objects of wonderment and dominance.

These recent reckonings with the monument challenge and invert the gaze that many monuments, including those commemorating white supremacy and settler colonialism, presume. If it is not necessary that all monuments must fall—and it might well be so—at the very least, we would do well to appreciate that, despite their supposed silence, monuments are in fact speaking to us all the time, informing our sense of history and overseeing a social order that their erectors took great pains to preserve. In the midst of this loud and heavy silence, we now, with a more inclusive and just notion of a public, are entitled to speak back to history, to contemplate our desires for monuments and create new visions of an accountable and ethical future.

[1] Eric Foner, “Confederate Statues and ‘Our’ History,” New York Times, August 20, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/20/opinion/confederate-statues-american-history.html

[2] Ibid.

[3] Benjamin Sutton, “Over 120 Prominent Artists and Scholars Call on NYC to Take Down Racist Monuments,” Hyperallergic, December 1, 2017. https://hyperallergic.com/414315/over-120-prominent-artists-and-scholars-call-on-nyc-to-take-down-racist-monuments/

[4] ibid.

[5] Kristina Killgrove, “Scholars Explain the Racist History of UNC’s Silent Sam Statue,” Forbes (blog), August 22, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2018/08/22/scholars-explain-the-racist-history-of-uncs-silent-sam-statue/#22b55c3114fb

[6] Speech by Julian Shakespeare Carr at the unveiling of the monument, June 2, 1913, Julian Shakespeare Carr Papers, Box 4, Folder 26, University of North Carolina Papers, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/c1160e4341b86794b7e842cb042fb414.pdf

[7] Ethan Woo, “Plaque commemorating Lenape people Unveiled after Three Years of Advocacy,” Columbia Daily Spectator, November 14, 2016, https://www.columbiaspectator.com/news/2016/10/11/plaque-commemorating-lenape-people-unveiled-after-three-years-advocacy/

[8] “Ti-Rock Moore,” Jonathan Ferrera Gallery, http://www.jonathanferraragallery.com/artists/ti-rock-moore/featured-works?view=slider

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.