Sugar, Subjection, and Selfies: The Online Afterlife of A Subtlety

Kara Walker’s installation art redeploys racist imagery in ironic and absurd cacophony. Since her rapid rise to fame—she won a MacArthur “Genius” grant in 1997—she has been celebrated and lamented in equal measure. What cultural critic Henry Louis Gates calls a postmodern critique of the horrors of the plantation, the artist Betye Saar sees as a reinscription of white supremacist fantasies of black animality and lasciviousness.[1] In 2014, Walker gained a new level of prominence with her installation A Subtlety: Or The Marvelous Sugar Baby. In characteristic Walker fashion, the full title continues: an Homage to the unpaid and overworked artisans who have refined our sweet tastes from the cane fields to the kitchens of the new world on the occasion of the demolition of the Domino sugar refining plant.

Photo: Jason Wyche. Artwork © 2014 Kara Walker

Walker transformed Brooklyn’s iconic Domino Sugar Factory into a gallery space that housed the “marvelous sugar baby,” a sculpture roughly 70 feet long and 35 feet tall. Made of polystyrene foam coated in white sugar, the sculpture depicts a “mammy-sphinx,” naked except for a kerchief tied around her head, breasts and genitalia exposed. As audiences approached the sculpture, they would first encounter thirteen figures of young boys, built to scale. Looking undernourished and carrying baskets for harvesting sugar cane, the figures were made of either dark brown resin or molasses. Drawing a series of connections—between stereotypes like “mammy,” the hypersexualization of black women, the history of enslaved labor in sugar production, and the gentrification of Brooklyn—A Subtlety crystallizes the way representations both enable and reproduce material injustice and structural violence.

Author’s screenshot of Creative Time’s website

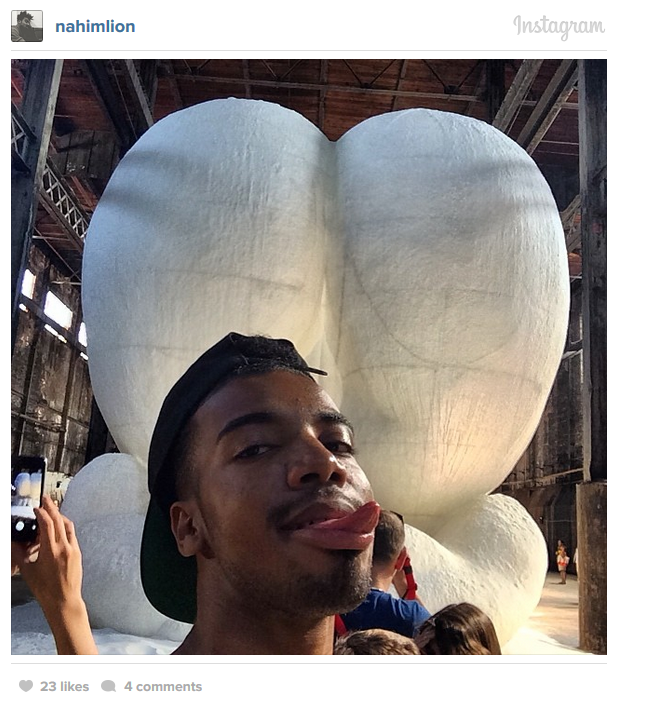

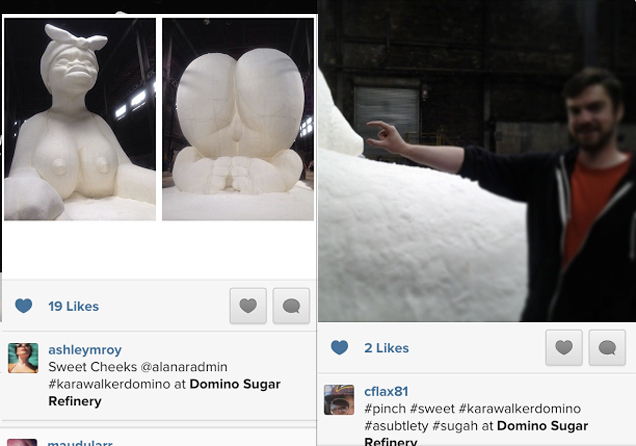

As central to the installation as the Sugar Baby, the molasses boys, and the factory itself, I argue, were the audience members and the images of the show they shared on social media. The show was free and open to the public, and the company that commissioned the work, Creative Time, encouraged patrons to share images of the work with the hashtag #karawalkerdomino. Creative Time planned, at least ostensibly, to create a digital replica of the sugar baby composed of patron-generated images. But as many media outlets quickly noted, visitors’ photos were often insensitive or offensive. They sexualized the sugar baby, “recreating,” as Nicholas Powers puts it, “the very racism this art is supposed to critique.”[2] Powers is right, of course, but I want to argue against the notion that the reproduction of violence in the gallery and the installation’s online afterlife is exclusively a sad symptom of continued pervasive racism.

Instagram capture via Artnet

It absolutely is. But it’s also a central part of the work, as Walker’s follow-up project, created from secret footage of the gallery, indicates. The installation’s afterlife—on Instagram, in online essays, and in Walker’s video—reframes the dynamic of violent spectatorship to turn the gaze on the viewers themselves. Thus, the figures we must engage with are not only the Sugar Baby and the molasses boys, but the audience members, who experienced a wide variety of emotional responses as they stood in reverence at the foot of the sculpture, smiled beside a molasses boy, pretended to fondle the Sugar Baby’s breasts, got distracted by their children, glanced nervously at their dates, and were hangry after standing in line so long. As all of Walker’s work does, A Subtlety pressures the distinction between represented and experienced violence. It also raises questions about the right and wrong way to look at art, engage with representations of suffering, and display emotions.

Instagram capture via Artnet

In its critical reception, A Subtlety appears to be one of Walker’s least controversial works. I’m sure it outrages Walker’s longtime critics, including Betye Saar, but nearly everything I’ve read about the installation understands its anti-racist claims to be fairly straightforward, and few claim that it, as Howardena Pindell has said, “caters to white fantasies of black bestiality.”[3] Instead of blaming Walker for irresponsibly reanimating minstrel-like stereotypes, writers overwhelmingly condemn audience members for having the wrong response to the work.

A notable exception is Nicholas Powers, who places the responsibility for audiences’ racist reactions to the work at the feet of Walker and Creative Time. He distinguishes between his own viewing experience, grounded in a collective “historical vision” that makes it impossible for black viewers not to see the centuries of suffering carried in the piece, and that of many white visitors to the exhibit, who, protected by the ignorance that is one of many privileges bestowed by white supremacy, could do things like photograph their children “smiling next to a slave boy.”[4] Powers argues that Walker should have curated the piece in a way that would clearly indicate the history it memorializes, one characterized by slavery, rape, and violence, in order to control audience reactions and prevent callous misreadings.

Yet as Saidiya Hartman has argued, spectacles of violence against black people have always provoked a range of responses. Even the most gruesome depictions of slavery, designed to convince audiences of its horror, risk making dehumanizing violence more familiar and acceptable.[5] As Elizabeth Alexander puts it, “Black bodies in pain for public consumption have been an American national spectacle for centuries.”[6] Given our collective history of racial spectacle, I can’t imagine what Walker or Creative Time could do to enforce the correct emotional response to the work, and I’m cynical enough to suspect that the more reverential gaze Walker’s work receives in museums is a product of the aesthetic disposition, rather than an ethical engagement with the suffering she depicts.

A Subtlety restages what Hartman has called “scenes of subjection” to realign affect and identity. Like Walker’s silhouettes, which obscure relationships between bodies and incorporate humorous and absurd elements to re-present plantation violence, A Subtlety employs legible symbols of slavery—the sugar baby’s knotted kerchief, the molasses and resin boys’ sugar baskets, which were slowly filled, over the course of the exhibit’s run, with the melted arms and heads of other molasses boys—but withholds narrative structures designed to elicit only sympathy or anger. Rather than a realistic or even allegorical depiction of the plantation, Walker uses icons and symbols in unfamiliar juxtapositions to scramble the distinction between the past and the present, between sculptures of enslaved boys and contemporary Dominican sugar workers,[7] and between the literal violation of black women and the symbolic violence enacted by stereotypes like “mammy” and “jezebel.”

Just as we might ask, “what is the relationship between eating sugar (or buying clothes, or meat, or fruit, or iPhones) and inflicting violence on others?” so does A Subtlety’s online afterlife ask, “what is the relationship between misreading art and reproducing symbolic violence against black people?” There is a disconnect between “insider” approaches to A Subtlety and the public response to it: for the show’s artist, producers, and professional critics, A Subtlety is deeply embedded in a legible historical context that straightforwardly indicates the gravity of the work and its relationship to continuing systems of injustice. Its wounds, in other words, are obvious and immediate. Yet for many viewers, their experience (at least as it was captured on Instagram) seemed totally distinct from and ignorant of the work’s relationship to violence.

If anyone was surprised by audiences’ public performances of violence, it was not, I suspect, Walker herself. In a show focused on the creation and aftermath of A Subtlety, Walker debuted a video produced from footage she was secretly taking of the gallery space. Titled An Audience, the video complicates the tragic narrative of the public’s engagement with A Subtlety. Rather than simply indicting audience members who took the wrong approach to the work, the video shows many viewers who exhibited earnest engagement with the work, appeared to take it seriously, and also smiled for the camera in front of the Marvelous Sugar Baby. Children dipped their hands in the puddles of molasses on the floor—in the blood, we might say, of those other children memorialized by the piece—and their parents laughed. These interactions with the work don’t fit so seamlessly into a framework that says there’s a right and wrong way to look at depictions of slavery, and that the distinction between them is obvious.

They also introduce a new wrinkle to the discussion of looking that A Subtlety prompts: when the gaze is redirected at the public, how are we to read bodies and faces? How are we to make interpretive claims about the emotional relationship between viewers and the artwork? What is the right way to look, and to appear to look, at this scene of subjection? We have models of it in some of the essays that appeared in response to the show: sadness, anger, and outrage are key emotions for encountering representations of historical violence and, indeed, of symbolic violence. The Marvelous Sugar Baby foregrounds the symbolic violence of Aunt Jemima as interlocked with the material violence of the plantation house and the cane fields. Yet the Sugar Baby also embodies power, authority, and refusal in its size, inscrutable expression, and right hand, which makes a “figa” symbol—a hand gesture that in Portuguese and Brazilian culture can mean both “good luck” and “fuck you.”[8] The sugar sphinx recalls the riddle Oedipus solved, one which required “a capacity for self-knowledge, self-recognition, [and] the ability to see oneself in the representations of others.”[9]

This works as a metaphor for the show’s engagement with its audience. Even though A Subtlety directly invokes sugar’s connection to the slave trade, the show’s online afterlife suggests that many viewers didn’t figure out the riddle. Instead of meditating on the relationship between sugar and slavery, represented and real violence, and their own complicity in these issues, many audience members merely joined the latest tourist spectacle, seeing and being seen. Instead of sadness, anger, or shame, evidence from Instagram suggests that emotions like delight and insouciance more frequently circulated in the gallery space.

Alongside racist and clueless interactions with the work, there was also resistance: New York artists Ariana Allensworth, Salome Asega, Taja Cheek, and Sable Elyse Smith organized the We Are Here event, which encouraged people of color to gather at the show on June 22, 2014 in order to “reject the uninformed and insensitive visual representations that have surfaced on social media” and “overwhelm this imagery with images and information grounded in respect and thoughtfulness.”[10] By crowding out the selfies that displayed racist and sexist interactions with the work, We Are Here also realigned the visual sphere of the show, both in the gallery and online. The online afterlife of A Subtlety highlights the racialized and embodied nature of looking; as Nicole Fleetwood argues, the visual sphere racializes those who look as much as it does those who are looked at.[11] Given the multicultural groups that visited the Domino sugar factory for the exhibit, the implications of the racialized gaze emerge in a complex cultural moment where we’re encountering Rachel Dolezals and George Zimmermans—figures that disrupt the persistent sense of American race relations as binary.

As Walker puts it, the installation “wasn’t just going to be about, ‘We’re all [messed] up and we’re all gonna die and we’re all trafficking in other people’s bodies.’ [Laughs.] We were also building something fantastic. So I had to go with that spirit: ‘We’re going to change the world and we’re going to do it like this!’”[12] We can think of her work’s public life and its online afterlife in an analogous way: #karawalkerdomino confirms that many folks in Brooklyn still find the minstrel show hilarious, but A Subtlety also carved out space in the art world for people who are typically outside of it. By redirecting the gaze onto the audience, A Subtlety’s online afterlife also linked how people look—at images of black suffering, at art, at racial signifiers—with how people look while they’re looking. #Karawalkerdomino offers evidence of white cluelessness and reenactments of racist and sexist violence, while An Audience and We Are Here provide counter-evidence of multicultural viewers experiencing a wide range of complex responses to art. These phenomena take Walker’s interest in the contingency of blackness and whiteness to new territory: not the silhouette, evacuated of color, but the body itself, the way it moves through the world, registers emotion, and experiences pain and pleasure.

[1] Gates, Henry Louis, and Betye Saar, qtd. in Anonymous, “Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroes.” International Review of African American Art 14.3 (1997). 2. The giant sugar sphinxffective responses to scenes of subjection foregrounds a video aragraphs as units of the argument or narr

[2] Powers, Nicholas. “Why I Yelled at the Kara Walker Exhibit.” The Indypendent. 30 Jun 2014. Web. https://indypendent.org/2014/06/30/why-i-yelled-kara-walker-exhibit.

[3] Pindell, Howardena. Qtd. in Als, Hilton. “The Shadow Act.” The New Yorker. 8 Oct 2007. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/10/08/the-shadow-act.

[4] Powers.

[5] Hartman, Saidiya. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. 2.

[6] Alexander, Elizabeth. “‘Can You be BLACK and Look at This?’ Reading the Rodney King Videos.” Public Culture 7 (1994). 77-94. JSTOR. 78.

[7] Danticat, Edwidge. “The Price of Sugar.” Creative Time Reports: Subtlety Series. 5 May 2014. http://creativetimereports.org/2014/05/05/edwidge-danticat-the-price-of-sugar/.

[8] Ball, Charing. “Why the Behavior of White People Shouldn’t Be Policed at the Kara Walker ‘Sugar Baby’ Exhibit.” Madame Noir. 3 Jul 2014. http://madamenoire.com/444739/white-people-policed-kara-walker-exhibit/.

[9] Russell, Francey. “Kara Walker: A Subtlety at the Domino Sugar Factory.” Los Angeles Review of Books. 20 Jun 2014. https://lareviewofbooks.org/essay/kara-walker-subtlety-domino-sugar-factory.

[10] Allensworth, Ariana, et. al. “Statement of Intent.” We Are Here. http://weareherekwe.tumblr.com/statement.

[11] Smith, Shawn Michelle. “Introduction: Visual Culture and Race.” MELUS 39.2 (Summer 2014). 1-11. Project MUSE. 3.

[12] Miranda, Carolina. “Kara Walker on the Bit of Sugar Sphinx She Saved, Video She’s Making.” Los Angeles Times. 13 Oct 2014. http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-kara-walker-on-her-sugar-sphinx-the-piece-she-saved-video-shes-making-20141013-column.html.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.