From Hopper’s Hollywood to Trump’s America

In 2011, when my book Hedda Hopper’s Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism came out, one of the first reviews was in the Wall Street Journal. Recently bought by right-wing media mogul Rupert Murdoch, who also owns Fox News, and known for its conservative editorials and opinions, the Wall Street Journal seemed to be the perfect place for a review. I’d long thought that contemporary American conservatives could learn a lot from the career of Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper.

Hopper was fifty-two years old and an underemployed, struggling supporting actress when her fledgling movie gossip column “Hedda Hopper’s Hollywood” was picked up by the Los Angeles Times in 1938. She soon became a powerful figure in the film industry during its golden age when the movies were the dominant form of mass entertainment in the United States. Her column was syndicated in eighty-five metropolitan newspapers as well as small town dailies and weeklies during the 1940s. In the mid-1950s, Hopper had an estimated daily readership of thirty-two million (out of a national population of 160 million) and remained influential into the next decade.

The staple of Hopper’s column, as with all Hollywood gossip and fan magazines, was the ostensibly private lives and personal problems of Hollywood stars. The stars needed good publicity and feared bad publicity, and Hopper’s gossip could provide both. Most of her gossip was favorable, as she needed to support the motion picture industry upon which she depended. Yet she also enjoyed her role as a scandalmonger. By positioning herself as the voice of small-town America, Hopper used her column to express what she saw as proper mores and values. She advised and chastised the residents of “Hollywood Babylon” about their behavior, actual and alleged. Facts didn’t stand in the way. “That’s the house that fear built,” she used to say of her Beverly Hills home.

Hedda Hopper at her office, 702 Guaranty Building, Hollywood Boulevard, 1945. (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

Hopper in her famous hats became a Hollywood icon, yet when I started working on my book few recognized her political significance. Hopper’s distinctive contribution to US popular and political culture between 1938 and her death in 1966 lay with how she combined and wielded gossip from the worlds of both entertainment and politics in her column. Always a conservative and a proud, active, and highly partisan member of the Republican Party, she used her journalistic platform to promote her political values and candidates and to assail liberals and leftists. In the process, she distinguished and propelled her career and pushed her agenda of political conservatism with her vast readership.

Hopper’s blurring of the boundaries between celebrity gossip and conservative politics presaged the kind of candidates, style of campaigning, and media figures increasingly prominent on the political right. Radio show host Rush Limbaugh had dominated the right-wing media ecosphere since the 1980s with personal insults rather than political substance. And in 2008 the Republican Party nominated for vice president Sarah Palin, who made up for her lack of political knowledge and experience with personal attacks and “zingers” aimed at her Democratic opponents. By 2011, when my book was published, Palin was a reality show personality. For these reasons, I thought a review in the Wall Street Journal would reach an audience potentially interested in one of Limbaugh and Palin’s predecessors. I should have known better.

The review started off badly and only got worse. My book, it turns out, gave the reviewer “indigestion” for “tearing down Miss Hopper because of her proudly conservative views.” Rather than citing any concrete evidence from the book for this claim of my “animus,” the reviewer referenced my previous book about the New Left in the 1960s and the wording of the book’s dedication to my mother. He got an important factual point wrong; I consider Hopper a feminist, but he claimed I called her antifeminist. And he ended with a personal attack. “Ms. Frost, a self-described ‘women’s historian,’ brings the intellectual habits of the faculty lounge to her work.” Caricaturing, carelessness with facts, making claims without evidence, and confirmation bias were on full display. It was a style of commentary not unlike Hopper’s own. The reviewer: Richard Carlson, the father of Tucker Carlson, who displays the same style on his Fox News show every night.

Such disregard for civility and the standards of public discourse was exceptional in Hopper’s heyday and earned her much criticism—even from her readers—but today it is all too common among right-wing figures. Such disregard contributed to the political rise of one of the biggest fans of Tucker Carlson’s show, Donald Trump. In turn, Trump perfected the synthesis of celebrity culture, gossip, and right-wing politics pioneered by Hedda Hopper a half century earlier.

Celebrity Culture

Born Elda Furry in 1885 to strict Quaker and Republican parents, Hopper gravitated to celebrity culture as a girl growing up in Altoona, Pennsylvania. She was fascinated with fashion and performance, loved reading the theater news and gossip in the Sunday papers, and dreamt of Broadway stardom. Without her parents’ prior knowledge or approval, Elda first joined a theatrical troupe in Pittsburgh, then arrived in New York in 1908. At age twenty-two, she signed on and toured with various opera companies as a chorus girl. Known for her beauty and poise, she eventually worked her way up to larger roles in plays and musical comedies. But she was not known for her singing, dancing, or even acting ability, and she knew it. “I was working under one handicap,” Hopper recalled. “No talent.”

She persevered in her theatrical career and in the process met her future husband, De Wolf Hopper. A famed stage actor, singer, and comic opera star, De Wolf was fifty-five when they married in 1913; Elda was half his age. She changed her name to “Hedda,” and the alliteration with her new husband’s last name worked. Although their marriage was sad and often humiliating due to De Wolf’s infidelities and insults, she gained celebrity and a growing film career. After their divorce in 1922, Hedda Hopper moved to Hollywood and, with a coveted studio contract at Metro-Goldwyn Mayer, perfected the role of the snobby society matron in some one hundred films. Her typecasting didn’t play well in the grim days of the Great Depression, however. In the 1930s, her career slowed, and she lost her contract.

Hopper struggled over the next years to find work and financial security, but by 1938 she succeeded in parlaying her movie celebrity and role as a Hollywood insider into a gossip column. She quickly established herself as a player in the competitive world of celebrity journalism and a rival to Louella Parsons, already a Hollywood gossip powerhouse. Bringing her classy, catty acting persona to her column, Hopper’s gossip career took off in the 1940s. Readers loved her candid comments, biting wit, and personal style. As an actress, she was comfortable with public display and attention getting, and nowhere were these characteristics more apparent than with her trademark: her famous hats. She became wholly identified with fashionable and flamboyant hats and earned titles such as the “Hollywood Hatter” and “Mad-Hatter Hopper.” Her celebrity grew.

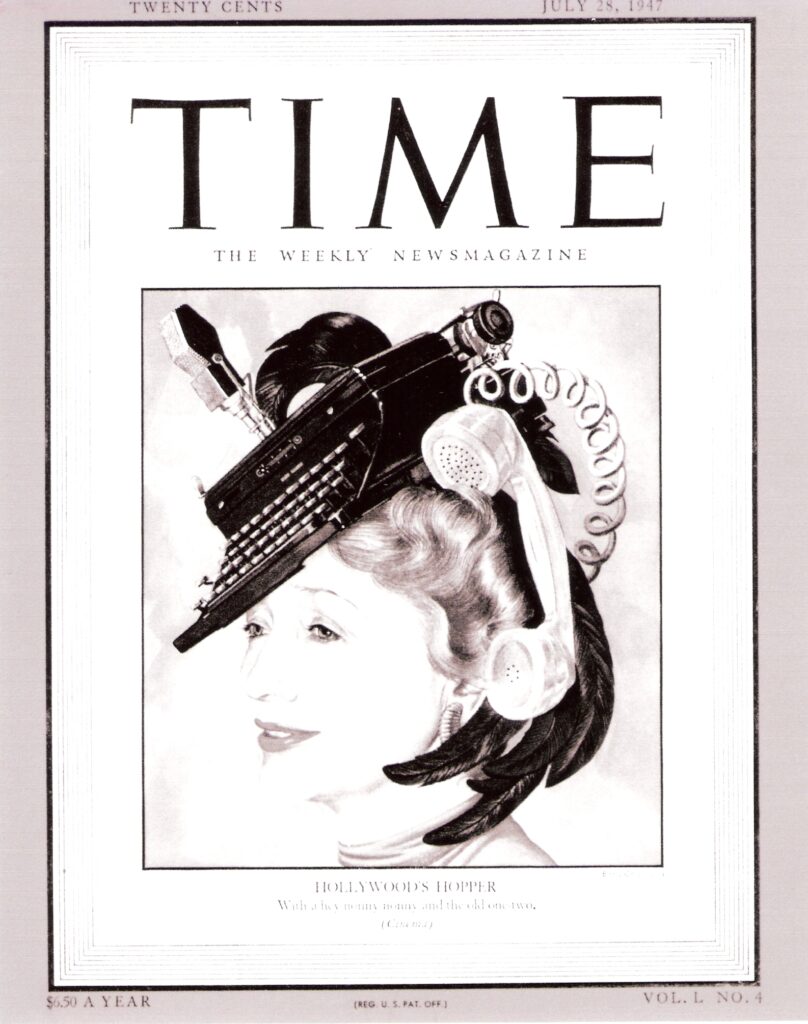

Celebrated for her accomplishments as a mass media gossip, Hopper also became known for her “well-knownness,” to quote historian Daniel J. Boorstin’s famous formulation of celebrity.[1] The media reported on her public activities and private life, and she was the subject of celebrity profiles. She even made the cover of Time magazine in 1947, portrayed in a crazy hat decorated with the tools of her trade: a telephone, typewriter, and microphone. She also appeared in movies and on radio and later television as fictional characters and as herself. For nearly a decade, she hosted a radio gossip show. Hedda Hopper well understood how to use her celebrity to market multiple commodities: her gossip, the movie industry, and soon her politics.

The same could be said about Donald Trump. Early on, he recognized how celebrity could help with marketing his New York real estate business, while his image as a successful businessman formed the basis of his celebrity. Stamping “Trump” on buildings was only the beginning. Many businesses he invested in, from airlines and casinos to steak and vodka, got his name. Soon he and the rest of the Trump Organization realized that money could be made from licensing his name to other businesses. Even as his branded businesses went bankrupt, and the Trump products failed to sell, his name and celebrity proliferated.

Trump recognized that publicity was key to celebrity from the beginning of his career in the 1970s. Despite inheriting the family real estate business and hundreds of millions of dollars from his father, he presented himself as a “self-made man” and savvy entrepreneur. And he eagerly participated in celebrity culture to create and promote this image. Most prominent was his relationship with the local and national tabloid press, such as The New York Post and The National Enquirer. He fed these and other media outlets information about his business deals and luxurious lifestyle, and their readers ate it up. Establishing his place at the pinnacle of the very rich and very famous was his 1987 bestselling, self-branded book written by Tony Schwartz, Trump: The Art of the Deal.

Despite a rocky road in the 1990s, when Trump filed for multiple bankruptcies and faced financial ruin, he emerged to become a reality show star on The Apprentice, starting in 2004. This rise from the ashes is typical of the celebrity profile, and he played it well. Even though his business finances had not yet recovered, he and his producer Mark Burnett presented him as back on top after persevering and fighting back. The Apprentice, on which he starred for a decade, allowed him to regain his status and reputation as a successful, swashbuckling businessman. Contestants competed for the opportunity to work for the Trump Organization, and he relished telling the losers, “You’re fired.” Very tellingly, the first losers Trump fired were often the most elite and arrogant contestants, conveying to his audience that he would take aim at those they despised.

What both Hopper and Trump shared—in addition to their multi-platform celebrity—was an understanding of how celebrity culture builds a personal connection between the star and their millions of fans. For Hopper, it was her readers. She worked hard to convey a sense, however false and manufactured, of familiarity and friendship. As in a conversation, Hopper inserted herself into her column by providing information about her life. She reported on her hairstyles and hats, the condition of her office and where she lunched. Trump’s presence on The Apprentice also furthered the idea that his viewers not only knew him but liked and trusted him. Both, in turn, would motivate and mobilize their fans toward political ends. In fact, Trump’s voters are best characterized as “fans”—active, enthusiastic, excessive, supporters.[2] Less charitably, their fandom conveys irrationality, emotionality, and even hysteria, from the original word: “fanatic.”

Gossip

Donald Trump and Hedda Hopper shared another insight: the power of gossip. When Hopper became a celebrity journalist in the late 1930s, she entered a well-established field. As historian Charles L. Ponce de Leon demonstrates, celebrity gossip, news items, and feature stories already were a “staple of the metropolitan press” by the 1880s, as “entertainment values became increasingly emphasized” in print journalism.[3] Mass media gossip had many of the characteristics of traditional gossip that make it an important and influential means of communication. Gossip is “private talk”—true or false talk about private life—voiced, often illegitimately, in the public realm. Although gossip historically has been seen as the private talk of women, it was a male columnist, the New York-based Walter Winchell, who took gossip into the mainstream of American journalism in the 1930s. Hopper adopted his hybrid of so-called “soft,” or entertainment, news and “hard,” or political, news.

Hopper understood that gossip had a crucial public function, with both positive value and negative ramifications. As in traditional societies, gossip in the mass media resulted in shared information and knowledge, allowed for discussion and exchange, and contributed to relationships and a sense of community among participants. Gossip also could be wielded as a weapon to assail the powerful in society and to reinforce dominant norms by stigmatizing those celebrities who stepped outside the boundaries of what the community deemed appropriate behavior. Hopper felt fully justified in publicizing private talk. She considered invasions of privacy in the interests of democracy; her readership had a “public’s right to know” about prominent figures.[4]

Hedda Hopper broadcasts her radio gossip program on NBC, [1943]. Photographed by Len Weissman. (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

One sensational incident later in Hopper’s career illustrated the practice and power of gossip. Early in September, 1958, Hopper published a front-page story detailing the romantic triangle Hollywood had been whispering about for weeks. The triangle involved the married couple, actress Debbie Reynolds and singer Eddie Fisher, and the “other woman,” actress Elizabeth Taylor. Starting with that first column in September, Hopper covered the Reynolds-Fisher divorce and the new couple’s wedding. In response to her articles, she reported that “the mail started arriving in stacks, all in Debbie’s favor.” As for Taylor, the “women of America” were “ready to all but stone her.” Hopper’s reader-respondents expressed concerns about the influence of Hollywood stars’ immoral behavior. As one asked about Taylor, “if she gets by with this thing, with our youngsters watching to see what happens, how are we going to say the good girl eventually wins and the bad girl loses?” They also pledged to boycott Taylor’s films and Fisher’s television show and his sponsors, and, in the end, Fisher lost his television show in the furor.

Celebrity gossip was a powerful discourse in Hopper’s time that has since proliferated across and permeated mass media outlets, particularly in the 1970s, just as Donald Trump took over the family business. The National Enquirer shifted to “personality journalism” in 1967, while the launching of People magazine in 1974 glossily perfected it. Trump forged a strong friendship with David Pecker, publisher of The National Enquirer, and made the cover of People on several occasions. His personal relationships with women, including his three wives, made headlines. When he felt coverage was flagging or less than favorable, he did not hesitate to take matters into his own hands. Pretending to be a publicist called “John Barron,” Trump made calls to reporters to generate coverage, often with “fake news.” He lied about his personal wealth in 1984 to get on the Forbes 400, a list of the richest people. In 1990, in the midst of a battle over his first divorce, he lied to the New York Post about reports of his sexual prowess, which the newspaper saw fit to publish.

Hopper also made false claims in her column, knowingly and not, but never as flagrantly as Trump does. As a publicist of private talk in America’s movie capital, Hopper included items intentionally designed to sustain fictions, like the happy marriage of Hollywood couple or the heterosexuality of a gay star. Through innuendo and association, she hinted at hidden truths and outright lies. There also were times when Hopper published gossip that turned out to be wrong. Local newspaper editors regularly cut items considered too controversial or potentially libelous from her column. At times, she was forced to print retractions and even apologize to those she smeared. She also was forced to settle a 1964 libel suit after she couldn’t prove true her accusation that actor Michael Wilding had a homosexual affair. This form of redress shows how the journalistic ethics and behavioral norms of Hopper’s era kept her in check.

But, in her willingness to push the boundary between fact and fiction, Hopper contributed to creating a public culture where a president could continually and compulsively lie (an estimated 30,000 times during the course of his presidency). Trump not only refuses to ever admit wrongdoing or remorse for doing so. Several times he threatened to “open up” US libel laws, so that he could more easily sue media publications for what he considered “fake news.” His threat never went anywhere, because the law already allows libel suits for injury due to false and defamatory statements. And if Trump took his case to court, his lawyers would have to prove true news stories false. That the former president lies with impunity while threatening the freedom of the press to tell the truth is not just hypocrisy but dangerous “gaslighting.”

In fact, the “Liar-in-Chief” lacks the personal sense of shame that made Hopper’s career as a purveyor of moral traditionalism possible. Hopper believed vehemently in sexual virtue for herself and others. When she arrived in the movie capital in the 1920s, the industry was in the midst of a “moral makeover” in the wake of several star scandals, the most shocking of which was the comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s arrest and trials for manslaughter in 1921 and 1922 due to the death of a young actress. As part of the makeover, the studios inserted “morals clauses” into employee contracts, allowing the studios to fire an employee for social or sexual impropriety or for causing a public scandal. For Hopper, the existence of morals clauses sanctioned her media exposure and moral judgment of private beliefs and behavior. A star who misbehaved was not only guilty of personal immorality but in legal violation of an employment contract. During the anticommunist blacklist era of the late 1940s and 1950s, the studios further invoked the morals clause to fire employees for what was deemed scandalous political behavior.

Both politics and morality were subject to Hopper’s public exposure and censure. She reveled in her role as a “moral gatekeeper”—but then so, too, do many contemporary conservative Christians. In support of Trump’s right-wing politics, would she have overlooked his moral transgressions, as do they? Perhaps so. She criticized how powerful, predatory men in Hollywood used and abused women through “casting-couch promiscuity”: giving or promising the woman a leading role in his latest film, having a sexual relationship, and then dropping her from the film and his life. She would have found allies in today’s #MeToo movement. That said, Hopper only went public in her criticism on these issues when the man in question had less power or more liberal politics than she did, a description that doesn’t fit Donald Trump.

Politics

Hedda Hopper would have enthusiastically endorsed Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy and campaign. His “Make America Great Again” agenda overlaps with her political ideology of Americanism. Liberty and freedom were at the heart of Hopper’s Americanism. She used these words to convey the basic right to live one’s life free of external restraints and to privilege independence and individualism over social qualities or collective interests. Like Trump, Hopper highlighted economic freedom, which she felt was threatened by “big government.” She resented the income tax and the welfare state. Trump brags about not paying his taxes: “that makes me smart,” he said in a 2016 debate. The only significant legislation he signed as president was a tax cut for the wealthy, while his federal budget proposals always included funding cuts for social programs.

Their divisive political agendas functioned, just like gossip does, to both include and exclude. In political speeches and actions, Hopper and Trump defined what and who was “un-American.” Both fervently believed that they stood and spoke for “real” Americans, so anyone who disagreed with them was, by definition, un-American. As Hopper avowed on her radio show in 1951: “This is the moment of Americans for America. The moment we all must stand and be counted. And let’s boot out the chiselers, the doubters, and the disloyal now.” In those categories were political liberals, whom she conflated with socialists and communists, a potent conflation at the height of the cold war. Ideological precision wasn’t her forte; neither is it Trump’s. In 2020, he accused his Democratic opponent, Joe Biden, of being a “pawn of socialists” and Biden’s running mate, Kamala Harris, of being “a communist.” Both Hopper and Trump were successful in persuading their fan base to conflate these three very different political ideologies and agendas.

They also proved persuasive in using nativism and racism to reinforce the boundaries between who gets to count as “American” and who does not. Trump’s political career and support originated in his racism. His full-page advertisements in New York newspapers in 1989 calling for the death penalty for five, as it turned out, innocent young African-American men wrongfully convicted of rape was only the beginning. His “birther” accusations that President Barack Obama was not born in the United States deployed both nativism and racism, as did his attacks on Mexicans at his presidential campaign launch in 2015. During his presidency, Trump operationalized his odious campaign promises, from his ban on (some) Muslim immigrants to building a (partial) wall on the southern border. Each racist and nativist action only endeared him more to his fan base.

Hopper’s nativist and racist campaigns similarly rallied her readers. Her attacks on immigrants and foreign visitors to the United States included a campaign against casting British actors in American movies. When Vivien Leigh won the starring role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939), Hopper considered it an insult to “every girl born here.” That an “unknown ENGLISH actress” would play “the most AMERICAN role of modern times,” reacted one reader: “No! A thousand times NO!” Hopper also used her gossip column to support African Americans in racially stereotyped screen roles. She advocated for a special Oscar for James Baskett, who portrayed Uncle Remus in Walt Disney’s Song of the South (1946), and in 1947 defended Hattie McDaniel’s portrayals of “mammies” in Gone with the Wind and other films. In these campaigns, Hopper pushed back against criticism of racial, and racist, stereotyping in Hollywood from civil rights organizations. These organizations, one reader noted, were “doing more harm than good. I don’t understand them.”

Hedda Hopper rides in an American Legion convention parade, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1941. (Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

Trump makes much uglier comments about today’s civil rights protests. Activists in the Black Lives Matter movement, according to Trump, are “terrorists” and “thugs.” It’s the protestors who are the problem, not racism or white supremacy. To any football player following Colin Kaepernick’s lead by kneeling during the national anthem to protest police brutality, Trump called, “Get that son of a bitch off the field.” That the president of the United States would use such profanity in public would have appalled Hopper, even as she used such language behind the scenes. In 1952, after her successful nativist and anticommunist campaign to chase out of the country the left-leaning English immigrant and filmmaker Charlie Chaplin, she wrote, “I abhor what he stands for.” Mistaking Chaplin as Jewish, she drew on anti-Semitic stereotypes, claiming he was stingy and selfish despite great personal wealth. More accurately, she cited his serial sexual and marital relations with women, particularly with young women, in her moral objections. “I would like to say ‘Good riddance to bad company.’” Two decades later, she referred to him more profanely in private. “I hear that son of a bitch Chaplin is trying to get back in this country. We’ve all got to work together to stop him!”

This common political style is as powerful a force as Hopper and Trump’s shared political agenda. Both debased political discourse. Rather than substantive discussions about politics and policy, they acted the bully, asserted fact-less opinions, appealed to emotions, and argued in simplistic slogans. Twitter’s 140 characters perfectly suited Trump’s crude political talk. His use of nasty nicknames for political opponents, even to those in his own Republican Party like “Lyin’” Ted Cruz and “Little” Marco Rubio, echoes Hopper’s use of personal attacks and character assassination. When liberal studio head Dore Schary took over Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1948, Hopper observed that “the studio will be known as Metro-Goldwyn-Moscow.” Linking liberalism to communism was a typical anticommunist move during the cold war. When Schary threatened to sue, the item was removed from future editions of her column. Action against Trump’s dangerous discourse in the form of a Twitter ban only came after the violent attempt at insurrection by Trump supporters on January 6, 2021.

But in both cases, such actions to limit their damaging political rhetoric reinforced their sense of grievance and victimization. Although belied by their persistent attacks and positions of power, Trump and Hopper always claimed to be on the defensive politically. Trump’s Twitter ban has been called “cancel culture” and, incorrectly, a violation of his right to free speech. Due to her conservative politics, Hopper believed, “I was almost thrown out of Hollywood.” Feeling victimized by the Democratic opposition, she considered herself an innocent, no matter what libelous words she used or alarming actions she took. Trump and his supporters, too, consider themselves on the defensive, claiming liberals and elites have all the power, and they have none. The content and style of Hopper’s politics are everywhere in Trump’s right-wing America.

Reactionary Nostalgia

At the heart of both Hedda Hopper and Donald Trump’s motivations and appeal is what’s best described as reactionary nostalgia. This kind of nostalgia links longing for the past, disappointment in the present, and fear of the unknown future. Through her constant references to an imagined, older world in her gossip column, Hopper constructed and repeated a narrative that presented the history of the United States as one of decline, due to the triumph of liberalism in politics and morality. With his 2017 inaugural address, “American Carnage,” Trump also criticized, and called for a conservative reaction to, changes in the country.

Yet neither nostalgic narrative, with their dark and pessimistic tones, won the support of a majority of Americans. Trump lost the popular vote in both the 2016 and 2020 elections, and his public opinion polling never got above a 50% approval rating. It’s useful to remember that Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again” originated with Ronald Reagan, who also shared Hopper’s Hollywood background. In 1980, when Reagan used a similar nostalgic narrative but added a resonant tone of hope, he took the White House and won the popular vote. Reactionary nostalgia for the America of yesteryear may have allowed Hopper and Trump to build their relationships with their fans. It certainly continues to provide an audience for Fox News and its media star commentators and potential politicos, like Tucker Carlson. But nostalgic commentaries that whitewash the past, disparage the present, and fear the future have limited appeal, at least for now.

Hopper’s career combining celebrity, gossip, and conservative politics prepared the way for the 45th president of the United States. Here’s hoping that Trump’s disastrous presidency and 2020 defeat has proven it isn’t the way forward ever again.

[1] Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, rev. ed. (New York: Atheneum, 1978).

[2] John Fiske, “The Cultural Economy of Fandom,” in Lisa A. Lewis, ed., The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (London: Routledge, 1992).

[3] Charles L. Ponce de Leon, Self-Exposure: Human-Interest Journalism and the Emergence of Celebrity in America, 1890-1940 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 43.

[4] Ponce de Leon, Self-Exposure, 41, 45.

Dilettante Mail

Get updates from us a few times a year.